Zubin Mehta’s Seventh: A Spirited But Uneven Dance with Beethoven

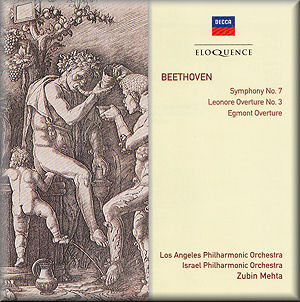

So here’s the deal with Zubin Mehta’s latest release of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, a 1974 recording that Universal Music Australia has decided to dust off and slap onto a compact disc. And let me tell you, they’ve managed to snag that rare quality we often crave in classical recordings—vitality. It’s not just a lifeless run-through of notes; there’s a spirited fun that makes you feel the music in your bones. But, let’s face it, I can’t help but compare this to other vintage late-analogue recordings, and that’s where the shortcomings start to poke through.

So here’s the deal with Zubin Mehta’s latest release of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, a 1974 recording that Universal Music Australia has decided to dust off and slap onto a compact disc. And let me tell you, they’ve managed to snag that rare quality we often crave in classical recordings—vitality. It’s not just a lifeless run-through of notes; there’s a spirited fun that makes you feel the music in your bones. But, let’s face it, I can’t help but compare this to other vintage late-analogue recordings, and that’s where the shortcomings start to poke through.

Now, don’t get me wrong. There’s beauty in Mehta’s interpretation, even if it doesn’t quite stack up against the likes of Toscanini, Munch, or Paray. These cats had a knack for showcasing the striking simplicity of Beethoven’s forte notation, and that’s something I hold dear. Then you’ve got Haitink’s London Symphony remake, which is a shining example of what happens when a conductor gives his musicians the freedom to breathe and inspire rather than just following the score like a robot.

Mehta may not be the polished gem of the conducting world, but his latest performance is a testament to his electrifying energy. It’s a worthy listen, and I’d say it even rivals some of his earlier works, which is saying something.

But when I think about Beethoven’s Fifth from the ‘70s, Herbert von Karajan’s second Berlin performance stands out for its precision, even if it struggles with orchestral blending. Stokowski’s interpretation, while a bit rough around the edges, still brings a unique charm that can’t be ignored. Taruskin, that sharp critic, points out the contrasting colors Karajan uses, which makes the music pop. And then we have this lively discussion about different interpretations of the vivace movement—some are energetic, others refined, but Mehta’s version? It’s a bit all over the place.

I can’t help but feel that Mehta’s interpretation lacks the meticulousness of Karajan’s, who masterfully utilizes the Philharmonie’s acoustics to create an awe-inspiring sound. Mehta’s straightforward approach is refreshing, but it sometimes feels like he’s overcooking the bar lines, losing the nuance that makes Beethoven tick.

And let’s not overlook the dynamic interplay between the horns and woodwinds; that’s the stuff that gives Beethoven’s work its richness. When done right, as in Giulini’s take, it transforms the piece into something truly special. Mehta, on the other hand, sometimes misses those moments of brilliance, and it’s a shame because they could elevate the performance to another level.

In the grand scheme, despite Mehta’s proficiency, he doesn’t offer anything groundbreaking. For the late analogue purists, Maazel and Karajan are still your go-tos for definitive performances. But hey, if you want to experience the raw intensity of Mehta’s Seventh, it’s worth a spin—just don’t expect it to dethrone the classics anytime soon. The vibrant musicianship and energetic attack are palpable, and there’s something to be said about that.

So here I am, tipping my hat to Mehta’s command of the classical repertoire, while still holding out for the next great rendition that’ll sweep me off my feet. Because at the end of the day, I’m still yearning for that perfect Seventh, and until then, I’ll keep my ear to the ground for the next gem to surface.