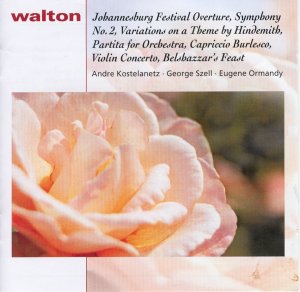

Composer: William Walton

Composer: William Walton

Works: Symphony No. 2, Variations on a Theme of Hindemith, Partita, Violin Concerto, Belshazzar’s Feast, Johannesburg Festival Overture, Capriccio Burlesco

Performers: Zino Francescatti (violin), Walter Cassel (baritone), Rutgers University Choir, Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy, Cleveland Orchestra, Georg Szell, New York Philharmonic, André Kostelanetz

Recording: Various sessions from the late 1950s to early 1970s

Label: Sony

William Walton, a towering figure in British music, has experienced a renaissance of interest, particularly on the centenary of his birth. His Symphony No. 2, composed during the late 1950s, stands as a testament to his evolving style post-World War II—a period marked by introspection and complex emotional landscapes. This collection, featuring seminal works like the Violin Concerto and a vibrant selection of orchestral pieces, exemplifies Walton’s distinctive voice that oscillates between exuberance and somber reflection.

The Symphony No. 2 serves as a striking contrast to its predecessor, infused with a darker, more turbulent energy reflective of the times in which it was composed. The first movement bursts forth with a frenetic intensity that recalls the wildness of the Johannesburg Festival Overture, yet here the exuberance is tinged with violence. Szell’s Cleveland Orchestra captures this dichotomy with precision, the brass sections particularly notable for their incisive articulation. The lento middle movement, infused with Baxian lyricism, offers a serene interlude that is both haunting and lush, showcasing Walton’s ability to weave profound introspection into his orchestral fabric. The finale, marked by raven-cawing trombones, reintroduces the earlier tumult, culminating in a powerful resolution that leaves the listener contemplative.

The Variations on a Theme of Hindemith is another standout piece in this collection, showcasing Walton’s adeptness at thematic transformation. The work, based on a motif from Hindemith’s Cello Concerto, reflects Walton’s deep respect for his predecessor while simultaneously asserting his own stylistic identity. The orchestral color is rich and varied under Szell’s direction, though the recording does reveal some pre-echo at around 16:20 that slightly detracts from the otherwise clear sonic landscape. This piece, though brief, encapsulates a serious symphonic character that belies its 22 minutes, making it an essential listen for those examining Walton’s mid-career development.

The Partita, commissioned for the Cleveland Orchestra’s fortieth anniversary, is a fascinating exploration of lighter material, yet it too hints at the weighty concerns that occupy Walton’s oeuvre. The oboe and viola lead in the Pastorale movement is a particularly charming instance of Walton’s lyrical gifts, evoking a Grecian warmth that invites comparison to Nielsen’s wind writing. Szell’s Clevelanders imbue this work with a buoyancy that is both playful and sophisticated, revealing the authentic Waltonian spark that resonates throughout the piece. The orchestration is deftly executed, and while the work may flirt with divertimento, the underlying shadows add depth to Walton’s lighter thematic explorations.

Francescatti’s interpretation of the Violin Concerto is electrifying; his performance is marked by a robust, character-driven approach that elevates Walton’s intricate lines. The vibrant, rough-toned quality of his playing is perfectly matched by the Philadelphia Orchestra’s responsive accompaniment under Ormandy, although the orchestral sound could benefit from a touch more clarity in the recording. The result is a compelling dialogue between soloist and ensemble that showcases Walton’s lyrical flair and technical demands.

Belshazzar’s Feast, although perhaps not the first choice for many, is presented here with a commendable vigor by the Rutgers University Choir, directed by F. Austin Walter. While the choir’s sound may feel somewhat smaller in scale compared to larger ensembles, their incisive enunciation and coordination shine through. The orchestral backdrop provided by the Philadelphia Orchestra is vibrant, delivering the work’s complex textures with clarity and impact. However, comparisons to EMI’s Previn-led recording reveal a greater sense of mass and volume in the latter.

This collection not only provides a broad view of Walton’s stylistic arc but also offers a tangible connection to the historical context of his works. The recordings, although derived from analogue sources, maintain a satisfactory quality that allows Walton’s rich orchestral palette to emerge effectively. Despite minor drawbacks in certain performances and the recording quality, this anthology serves as an invaluable resource for understanding Walton’s contributions to the 20th-century canon.

The breadth of this collection, featuring both early and late works, reveals a composer who continually evolved while remaining deeply rooted in his British identity. Walton’s music, with its vibrant orchestration and emotional depth, continues to resonate powerfully, making this collection a worthy addition to any serious listener’s library.