Composer: Richard Wagner (1813-1883)

Composer: Richard Wagner (1813-1883)

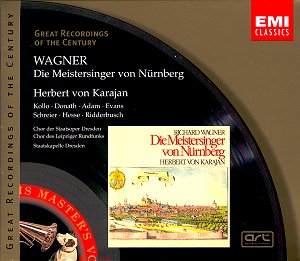

Works: Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (1862-1868)

Performers:

Choirs:

Orchestra:

Conductor:

Recording:

Availability: Crotchet £34, AmazonUK £36, AmazonUS $44.62

The 1970 recording of Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg under the baton of Herbert von Karajan, reissued as part of EMI’s Great Recordings of The Century collection, stands as an enduring testament to the conductor’s artistry and the rich historical context surrounding its creation. This rendition not only captures the essence of Wagner’s most light-hearted opera but does so against the backdrop of a divided Germany, with its recording in East Germany resonating as an emblem of cultural exchange amidst political dichotomy.

Karajan’s collaboration with the Staatskapelle Dresden—an orchestra steeped in Wagnerian tradition—proves to be an inspired choice. The opening prelude immediately reveals the warmth of the strings and the lyrical quality of the woodwinds, which Karajan describes as having a sound “like old gold.” This lush timbre is not simply a matter of aesthetic gloss; it enhances the narrative flow of the opera, setting the stage for the intricate interplay of musical themes that defines the work. The conductor’s “chamber music” approach allows the orchestral textures to shine through, presenting an engaging transparency that is often absent in more bombastic interpretations.

The character of Hans Sachs, masterfully portrayed by Theo Adam, emerges with a nobility that is both introspective and commanding. Adam’s interpretation eschews heavy dramatics, instead opting for a lyrical simplicity that aligns well with Wagner’s intentions. His delivery of the “Wahn” monologue in Act III, for instance, is imbued with a poignant restraint that invites listeners into the character’s inner turmoil, a choice that contrasts effectively with the more declamatory approaches of some predecessors. This focus on character nuance provides a refreshing depth to the performance.

René Kollo’s Walther von Stolzing presents an interesting case in this recording. While his youthful ardor and romantic phrasing are commendable, one might argue he lacks the vocal heft required for the Prize Song in Act III. Nevertheless, Kollo’s youthful vocality is a significant interpretative decision that aligns with Karajan’s preference for lighter voices, which allows for a more nuanced portrayal of the opera’s youthful lovers. Helen Donath as Eva complements Kollo’s portrayal, her initial hesitation in taking the role yielding to a performance that captures the character’s vivacity while maintaining a gentle charm.

Geraint Evans’ Sixtus Beckmesser is another standout performance within this recording. His distinctive “sing-speech” delivery embodies the character’s inherent pettiness without veering into caricature. This balance allows for a complex reading of Beckmesser, evoking both disdain and a modicum of sympathy as he navigates the opera’s social landscape. The interplay between him and Adam’s Sachs is particularly effective, allowing for a nuanced exploration of rivalry and camaraderie.

The engineering of this recording deserves special mention. Recorded in the Lukaskirche, the sound quality is superb, capturing the intricate details of the performance without overwhelming the listener. The balance between voices and orchestra is commendable, ensuring that the choruses—especially the riot scene in Act II—maintain clarity amidst the tumult. The spatial acoustics of the church enhance the ensemble’s sound, allowing for a sonorous yet intimate experience.

Historically, this recording is significant not only for its artistic merit but also for its cultural implications. The decision to record Meistersinger in East Germany during a politically charged era underscores the unifying potential of art. Karajan’s presence, a symbol of Western musical prestige, alongside East German artists, creates a palpable tension that adds layers of meaning to the performance. The historical context enriches the listening experience, inviting reflection on the role of music as a bridge between divided worlds.

In conclusion, Karajan’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg remains a reference point for interpretations of Wagner’s operas, successfully marrying musical integrity with historical significance. While some may prefer the immediacy of Karajan’s earlier Bayreuth recording, this version’s spaciousness and attention to detail render it an essential addition to any Wagnerian collection. The combination of an exceptional cast, a legendary orchestra, and Karajan’s insightful direction coalesces into a performance that is both revelatory and deeply satisfying, securing its place in the pantheon of great operatic recordings.