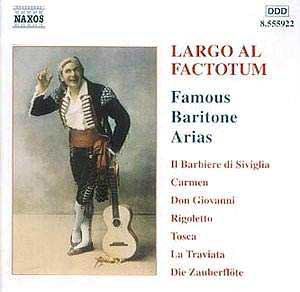

Composer: Gioachino ROSSINI, Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART, Georges BIZET, Giuseppe VERDI, Ruggiero LEONCAVALLO, Pietro MASCAGNI, Giacomo PUCCINI

Composer: Gioachino ROSSINI, Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART, Georges BIZET, Giuseppe VERDI, Ruggiero LEONCAVALLO, Pietro MASCAGNI, Giacomo PUCCINI

Works: Largo al Factotum, Der Vogelfänger bin ich ja, Se vuol ballare, Non più andrai, Hai già vinta la causa!, Deh! Vieni alla finestra, Non siate ritrosi, Votre toast, Pari siamo!, Cortigiani, vil razza donnata, Il balen del suo sorriso, Di Provenza il mar, Era la notte, Ehi paggio!, Si può, Il cavallo scalpita, Tre shirri, una carrozza

Performers: Roberto Servile, Georg Tichy, Natale De Carolis, Bo Skovhus, Andrea Martin, Alan Titus, Eduard Tumagian, Igor Morozov, Silvano Caroli, Domenico Trimarchi

Recording: Naxos 8.555922 [71.35]

Label: NAXOS

This compilation of baritone arias functions as a tribute to a voice type that has historically navigated a complex terrain of dramatic expression and lyrical beauty. Baritone roles, especially in the operatic canon, often oscillate between layers of nobility, villainy, and comedic relief—a dichotomy that composers like Rossini and Verdi have expertly exploited. The album features 20 selections, predominantly from the operatic repertoire, showcasing the strengths and shortcomings of various artists in bringing these iconic characters to life.

Roberto Servile’s performance of Rossini’s “Largo al Factotum” sets a high standard right from the outset. His agile coloratura and well-integrated voice convey both the character’s vivacity and the aria’s inherent humor, despite not matching the frenetic patter of renowned predecessors. Servile’s choices in dynamics and phrasing bring a refreshing clarity to the text, yet moments of vocal tension, particularly in his lower register, momentarily disrupt the otherwise seamless execution. Later, as the Count di Luna in “Il trovatore,” he displays a rich tonal quality in “Il balen del suo sorriso,” but his lower range lacks the necessary power, creating a slight imbalance that detracts from the emotional weight of the character.

Georg Tichy’s portrayal of Papageno offers a stark contrast. His robust voice lends itself well to the character’s jovial nature, yet lacks the youthful exuberance that is critical to the bird-catcher’s charm. While Tichy navigates the melodic lines with precision, his interpretation suffers from an over-theatrical attempt to lighten the vocal texture, which feels somewhat forced. The subsequent selection, Natale De Carolis’s interpretation of Figaro, similarly grapples with the need for playfulness. De Carolis’s rich sound is ideal for Mozart, but his consistently forte approach results in a missed opportunity to explore the nuanced dynamics that define Figaro’s character.

Bo Skovhus presents an aristocratic interpretation of Don Giovanni, particularly in “Deh! Vieni alla finestra.” His phrasing exhibits a commanding presence, although a slightly brisk tempo in “Finch’han dal vino” undermines the seductive swagger that the character demands. In contrast, Andrea Martin’s airy lyricism in “Non siate ritrosi” from “Cosi fan tutte” captures the youthful spirit of Guglielmo, despite a slight dryness in the lower register. The playful irony in his characterization, however, shines through, making this a notable contribution to the recording.

Alan Titus’s “Votre toast” from “Carmen” stands out as a disappointing moment within the collection, lacking the charisma and bravado expected of Escamillo. The performance feels flat and lacks the vibrant energy that would typically characterize a bullfighter, resulting in a portrayal that does not resonate with the depth of the character. Eduard Tumagian, on the other hand, brings a compelling dramatic flair to “Pari siamo!” from “Rigoletto,” skillfully blending lyrical lines with the jester’s inherent self-loathing. Yet, his interpretation falters in “Cortigiani, vil razza donnata,” where diction occasionally suffers, detracting from the emotional impact of the aria.

The engineering quality of this Naxos recording is commendable, capturing the nuances of each performance with clarity and balance. The orchestral accompaniment, provided by various ensembles, is generally supportive, though at times it threatens to overshadow the singers. The decision to scatter selections from multiple composers and time periods throughout the album results in a disjointed listening experience. However, this arrangement does expose listeners to a diverse range of interpretations, each illuminating different aspects of the lyric baritone’s capabilities.

This collection, while uneven, delivers moments of genuine artistry alongside performances that are merely adequate. The interpretations offer a profound insight into the lyric baritone’s diverse roles, balancing between comedy and tragedy in a manner that challenges and engages the listener. The album serves not only as an introduction to these iconic arias but also as a platform for emerging talents to explore the rich emotional landscape that the baritone voice can traverse.