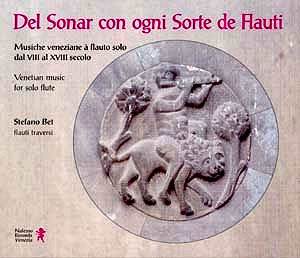

Composer: Venetian

Composer: Venetian

Works: Inni e Sequenze Anonimo veneto sec. XIV; Giorgio Mainerio: I° libro dei balli; Giovanni Bassano: Ricercata sesta; Silvestro Ganassi: Ricercare; Anonimo sec. XVI: Romanza ebraico-sefardita; Anonimo sec. XVIII: raccolta di balli; Benedetto Marcello: Sonata prima; Anonimo sec. XVIII: raccolta di balli; Pietro Grattoni d’Arcano: Sonata; Le Printemps de Vivaldi arrangé pour la flute sans accompagnement par Mr. J.J. Rousseau

Performers: Stefano Bet, traverse flutes

Recording: 1-3 September 2000, Chiesa di S. Trovaso, Venezia, Chiesa di S. Lorenzo, S. Vito al Tagliamento Frini (Italy)

Label: NALESSO NR 010

Stefano Bet’s latest offering, a compilation of solo flute music from the rich tapestry of Venetian history, reveals a commendable ambition to traverse centuries of repertoire. Encompassing works that date from the 14th century to the Baroque period, this recording seeks to illuminate the evolution of the flute as an instrument capable of both imitative and expressive capabilities. Bet’s selection, which includes Gregorian motets, lively dances by Mainerio and Bassano, and the vibrancy of Vivaldi’s “Spring,” serves as a vehicle to not only display the flute’s historical significance but also to explore its diverse sonic palette.

The initial offerings, steeped in Gregorian chant, while academically interesting, reveal the limitations of the flute’s early role as a voice substitute. Here, Bet’s approach is methodical, yet the performances lack the supple nuance that the sacred repertoire demands. This lack of engagement becomes more pronounced as the recording progresses. The lively 16th-century works, especially those by Mainerio and Bassano, should invigorate the listener with their rhythmic vitality and melodic inventiveness. Unfortunately, Bet’s interpretations feel constrained; the energy and buoyancy that should characterize such dances are absent. The phrasing tends toward the mechanical, often adhering too rigidly to a metronomic pulse that undermines the inherent expressiveness of the music.

Benedetto Marcello’s Sonata prima, the first multi-movement work on the disc, further highlights Bet’s interpretative shortcomings. While the Baroque idiom allows for greater rhetorical freedom and contrasts, the performance remains uninspired, lacking the dynamic shading and emotional depth that the music calls for. The four movements should convey a spectrum of feelings, yet Bet’s choices result in a sound that is at once wooden and unyielding, failing to engage the listener’s imagination.

The arrangement of Vivaldi’s “Spring,” though familiar, is treated with a similar lack of fervor. Rousseau’s transcription for solo flute offers a chance to explore the florid, pastoral lines of the original, yet Bet’s rendition is lethargic, stripping the music of its dazzling charm. The moments that should sparkle instead languish under a veil of indifference. The recording quality, though adequately capturing the acoustic of the venues, does not compensate for the performance’s lack of vibrancy. The engineering is clean, allowing the nuances of the traverse flute to come through, yet one longs for a more expressive interpretation that could truly utilize the instrument’s capabilities.

For flautists and scholars, this recording may hold some value due to its variety and historical scope, but for the general listener, the experience is unlikely to spark joy or curiosity. The juxtaposition of works from diverse centuries provides an interesting framework, yet the execution fails to elevate the material. The ennui that permeates much of the performance does a disservice to the remarkable repertoire it seeks to present. A more spirited, imaginative approach could have transformed this disc from a didactic excursion into a compelling musical journey. Bet’s endeavor, while ambitious, ultimately leaves an impression of missed opportunities and unfulfilled potential.