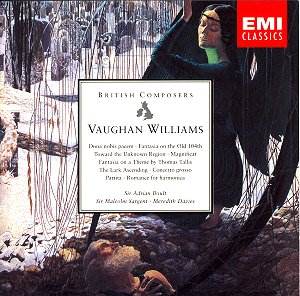

Composer: Ralph Vaughan Williams

Composer: Ralph Vaughan Williams

Works: Toward the Unknown Region, Dona nobis pacem, Fantasia (quasi variazione) on the Old 104th Psalm Tune, Magnificat, Partita, Concerto Grosso, Fantasia on a theme by Thomas Tallis, Romance in D flat, The Lark Ascending

Performers: Sheila Armstrong (soprano), Helen Watts (contralto), John Carol Case (baritone), Peter Katin (piano), Jean Pougnet (violin), Christopher Hyde-Smith (flute), Larry Adler (harmonica), Ambrosian Singers, London Philharmonic Choir, BBC Symphony Orchestra, London Philharmonic Orchestra, Orchestra Nova of London, Philharmonia Orchestra

Recording: Various dates between 1952 and 1975, Kingsway Hall, Abbey Road Studios, St. Augustine’s, Kilburn

Label: EMI

Ralph Vaughan Williams occupies a unique position in the pantheon of British composers, embodying both the pastoral ideal and a profound engagement with existential themes. This EMI collection presents a selection of his works that span his career, providing an insightful glimpse into his evolution as a composer. It is a testament to the composer’s exploration of diverse vocal and instrumental textures, as well as his willingness to fuse traditional forms with contemporary sensibilities. The inclusion of both well-known masterpieces and lesser-performed pieces serves to broaden the listener’s understanding of Vaughan Williams’s artistic trajectory.

The opening work, “Toward the Unknown Region,” is emblematic of Vaughan Williams’s early style, rife with Whitman’s unorthodox verse. While the orchestral and choral forces are ambitious, the performance under Sir Adrian Boult—who conducted the first performance—reveals a certain disjointedness, particularly in the early stages. The choir’s sound often feels scattered, lacking the necessary cohesion to convey the piece’s lofty spiritual aspirations fully. Boult’s interpretative choices, while imbued with conviction, do not elevate the work to its potential transcendence. The second part, however, finds a more compelling musical unity, showcasing the emotional depth that Vaughan Williams intended.

“Dona nobis pacem,” recorded in the same sessions as “Toward the Unknown Region,” emerges as a standout. This work’s synthesis of liturgical texts and Whitman’s poetry creates a poignant commentary on the human condition and the longing for peace amidst turmoil. Boult’s direction here is particularly effective; he draws out a visceral intensity from the performers, resulting in a harrowing yet cathartic experience. The interplay between the choir and the orchestral forces is more successfully integrated, allowing the piece’s thematic material to resonate deeply with the listener. The emotional weight carried by the text, especially the line “For my enemy is dead, a man as divine as myself,” serves as a profound reminder of our shared humanity.

“Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis” and “The Lark Ascending,” both iconic works, receive commendable performances. The Tallis Fantasia, despite being a staple of choral repertoire, retains its ability to enchant, particularly through the lush harmonies and intricate counterpoint. Boult’s interpretation conveys a sense of reverence, though it occasionally lacks the ethereal quality that more contemporary recordings might evoke. Similarly, Jean Pougnet’s take on “The Lark Ascending” feels slightly more literal than inspired, failing to capture the full poetic essence that this piece can evoke when performed with a more expansive vision.

The inclusion of the “Romance in D flat” for harmonica and orchestra is a delightful surprise, showcasing Vaughan Williams’s adventurous spirit in instrumental combinations. Larry Adler’s harmonica performance is particularly engaging, bringing a bittersweet quality that recalls the music hall tradition while blending seamlessly with the orchestral fabric. The recording quality, while reflective of its mid-20th-century origins, holds up well, allowing the nuances of the harmonica to shine through amidst the orchestral backdrop.

The collection’s technical aspects display a range of sound quality, with some recordings—particularly those from the late 1950s—exhibiting a clarity and warmth that enhance the listening experience. However, the earlier recordings, such as “Toward the Unknown Region,” occasionally suffer from a lack of sonic depth, which diminishes the impact of the orchestral textures. Comparatively, newer interpretations of these works frequently achieve a greater sense of spatial dimension, which is critical for fully realizing Vaughan Williams’s expansive sound world.

The compilation of these works, while serving as an informative survey of Vaughan Williams’s oeuvre, also raises questions about the interpretative choices made by the conductors involved. Boult’s performances are historically significant, yet they often stop short of fully realizing the emotional and structural complexities inherent in Vaughan Williams’s music. The inclusion of alternative recordings, particularly those by conductors like Sir Malcolm Sargent or more contemporary interpretations, could have provided a richer contextual background against which to appreciate the composer’s diverse output.

“Dona nobis pacem” stands out as the essential recording within this collection, encapsulating the profound humanism that Vaughan Williams championed throughout his life. The work’s urgent plea for peace remains as relevant today as it was at its inception, and this performance captures its essence with a clarity and intensity that are hard to surpass. The collection serves as both a valuable introduction to Vaughan Williams’s less familiar works and a reminder of the enduring power of his most celebrated compositions.