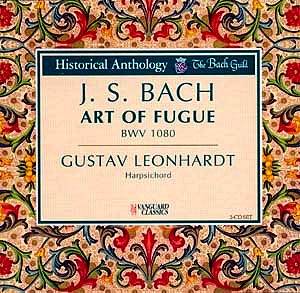

Composer: Johann Sebastian Bach

Composer: Johann Sebastian Bach

Works: The Art of Fugue BWV 1080

Performers: Gustav Leonhardt, harpsichord

Recording: May 1953, Vienna

Label: Vanguard OVC 2011/12 [86.56]

The Art of Fugue, BWV 1080, stands as one of Johann Sebastian Bach’s towering achievements, encapsulating the very essence of contrapuntal mastery. Written during the last years of his life, this collection of fugues and canons explores the depths of polyphonic texture while remaining enigmatic in its intended performance context. The work’s unfinished status casts a shadow of mystery, prompting varied interpretations, especially regarding the choice of instrumentation. Gustav Leonhardt’s 1953 recording, one of his earliest ventures into Bach’s oeuvre, is historically significant as it aligns with the burgeoning movement towards “authentic” performance practices that characterized the mid-20th century.

Leonhardt’s interpretation is marked by a profound understanding of the contrapuntal intricacies inherent in Bach’s writing. His decisions regarding tempo, while occasionally languorous—particularly in the fourth part, the Simple Fugue—allow for a meticulous exploration of thematic development. However, this approach risks veering toward didacticism, stripping the music of its inherent vitality and expressive potential. In contrast to his later recordings, this performance occasionally feels constrained, as if the harpsichord itself is struggling to convey the full emotional breadth of Bach’s intentions. The juxtaposition of slow tempi against the intricate interweaving of lines can lead to moments where the music feels less like a living entity and more like an academic exercise.

The technical quality of the harpsichord used in this recording presents a more significant barrier to appreciation. While Leonhardt’s artistry shines through, the instrument’s tinny sound lacks the depth and resonance that such complex music requires. Notably, the lower range proves particularly problematic; fugues employing these pitches often emerge thin and hollow, diminishing the impact of their contrapuntal interplay. This issue is compounded by the recording techniques of the 1950s, which, while pioneering at the time, do not measure up to contemporary standards. Leonhardt’s interpretation is at times marred by the instrument’s tuning problems, particularly evident in the unfinished fugue that closes the work, further complicating the listener’s experience.

When compared to more recent recordings, such as Davitt Moroney’s interpretation on Harmonia Mundi or Robert Hill’s version on Brilliant Classics, Leonhardt’s 1953 rendition reveals its age. These more recent performances benefit from not only superior instruments but also from advancements in recording technology that allow for a fuller, more vibrant sound. Moroney, for instance, exploits the tonal palette of the harpsichord to capture the nuanced dialogue between voices, whereas Leonhardt’s early efforts may lack the same clarity and warmth.

Leonhardt’s early recording of The Art of Fugue is a fascinating artifact that encapsulates a pivotal moment in the evolution of Bach interpretation. His insights into the music are commendable, revealing a deep engagement with the material. However, the limitations of both the instrument and recording quality ultimately hinder the performance from reaching its full potential. For those seeking a definitive harpsichord interpretation of this monumental work, it is advisable to explore more recent offerings that honor both the intricacies of Bach’s composition and the advancements in performance practice.