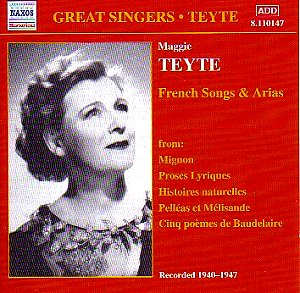

Maggie Teyte: French Songs & Arias [FC]

Maggie Teyte: French Songs & Arias [FC]

Recorded 1940-1947

ADD NAXOS HISTORICAL – GREAT SINGERS 8.110147 [66: 31]

Review by: Frank Cadenhead

Maggie Teyte’s anthology of French songs and arias, recorded between 1940 and 1947, offers a fascinating glimpse into a pivotal period of vocal art, where the French repertoire was performed with a sense of authenticity that is often lacking in contemporary interpretations. Teyte, a prominent figure in the early 20th century, is celebrated for her interpretations of French music, yet her recordings reveal both the triumphs and limitations of her artistry.

The repertoire is thoughtfully curated, showcasing a range of composers from the poetic lyricism of Duparc’s “L’invitation au voyage” to the vibrant colors of Ravel’s “Histoires naturelles.” These selections not only highlight Teyte’s command of the French song repertoire but also serve as a historical document of performance practices of the time. It is a reminder that prior to the mid-20th century, singers often specialized in the language of their performance, and Teyte was no exception.

In examining Teyte’s voice, it is evident that her interpretative choices convey an earnestness and dedication to the text. However, her instrument, while possessing a certain clarity, lacks the warmth and resonance that one might expect from a singer of her stature. For instance, in the aria “Connais-tu le pays?” from Thomas’ Mignon, the phrasing is articulated with a delicate sensitivity, yet the timbre does not evoke the lush emotional landscape that the music demands. This absence of warmth is particularly pronounced when juxtaposed with the recordings of her contemporaries, such as the radiant and expressive Felicity Lott or the rich-toned Jessye Norman, who bring a more nuanced color to similar repertoire.

Teyte’s diction, while understandable, does occasionally falter under scrutiny. Her pronunciation, described as “school-girl French,” suggests a lack of immersion in the phonetic subtleties that characterize French song. This is particularly apparent in her rendering of Debussy’s “Voici ce qu’il a écrit à son frère Pelléas,” where the melodic lines are undercut by an anglicized accent. A comparison with the effulgent clarity of a later artist like Natalie Dessay highlights this shortcoming, as Dessay achieves a perfect balance of musical line and linguistic authenticity.

The accompaniment, provided by the young Gerald Moore and, in some arias, Pierre Monteux with the San Francisco Symphony, is uniformly attentive and sympathetic. Moore’s pianism, in particular, complements Teyte’s interpretations, offering both support and a rich harmonic palette against which she can project her voice. In Hahn’s “Entre adoré,” the interplay between voice and piano is particularly striking, showcasing Moore’s deft touch and Teyte’s ability to float an ethereal line over the shimmering accompaniment.

Recording quality, typical of its era, possesses a certain charm, though it does not escape the limitations of its time. The engineering allows for a clear presentation of Teyte’s voice, yet the resonance and depth of the piano are occasionally muffled, diminishing the overall impact of the performances. Modern listeners may find themselves yearning for the dynamic range and clarity afforded by contemporary recording techniques.

Historically, this collection serves as a significant document of Teyte’s contributions to the French song tradition. Her connections with composers such as Debussy, with whom she collaborated closely, lend an authenticity to her interpretations that is invaluable. Works like Chausson’s “Les Papillons” and the poignant “Les temps des lilas” from Poème de l’amour et de la mer resonate with a sense of nostalgia for a bygone era, encapsulating the emotional essence of the French art song.

In conclusion, while Maggie Teyte’s recordings may not universally satisfy the modern listener seeking the warmth and sophistication of contemporary singers, they nonetheless present a rich tapestry of French vocal music that merits exploration. Her interpretations invite us to delve deeper into the nuances of French song and opera, offering a historical context that enriches our understanding of this repertoire. For those willing to engage with the past, Teyte’s collection serves as a valuable point of departure into the exquisite world of French lyrical expression.