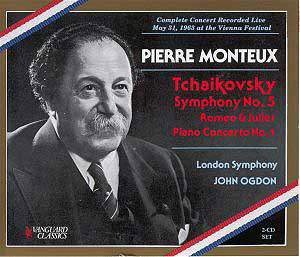

Composer: Tchaikovsky

Composer: Tchaikovsky

Works: Romeo and Juliet, Piano Concerto No. 1, Symphony No. 5

Performers: John Ogdon (piano), London Symphony Orchestra, Pierre Monteux (conductor)

Recording: Concert performance, 31 May 1963, Grosser Konzertsaal, Vienna, ADD

Label: Vanguard Classics OVC 8031/2

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s oeuvre remains a touchstone of the romantic symphonic repertoire, and this recent reissue of a live concert from 1963 under the revered baton of Pierre Monteux offers a compelling glimpse into the composer’s emotional depth and orchestral color. The works presented—most notably the iconic “Romeo and Juliet,” alongside the “Piano Concerto No. 1” and “Symphony No. 5″—reveal Tchaikovsky’s ability to encapsulate human experience through music. This recording, now resurfaced from archival obscurity, allows listeners to engage anew with Tchaikovsky’s passionate lyricism and Monteux’s masterful interpretative prowess.

The performance of “Romeo and Juliet” is particularly striking. Monteux commands the London Symphony Orchestra with a precision that marries structural clarity with an emotional arc that is both gripping and fervent. The strings are lush and resonant, their sonorous depth creating a palpable atmosphere of longing and tragedy. The climactic moments—like the heart-stopping crescendo at 14:20, where the love theme emerges—are executed with such intensity that they are bound to send chills down the spine of even the most seasoned listener. Monteux’s ability to build tension here is remarkable; he balances fervor with finesse, allowing the music to swell and recede in a manner that feels organic and inevitable.

In the “Piano Concerto No. 1,” John Ogdon’s performance is explosive, capturing the work’s inherent drama and virtuosity. While this interpretation may not reach the fiery heights of Petukhov’s live recording, Ogdon’s dynamic contrast and rhythmic vitality are commendable. The opening movement’s tempestuousness is matched by a delicate lyricism in the second movement, showcasing Ogdon’s technical prowess and interpretative depth. However, the recording’s impact is somewhat diminished in comparison to other notable renditions, which might offer a more nuanced balance between the soloist and orchestra.

The second disc’s presentation of the “Symphony No. 5” is where Monteux’s nuanced approach truly shines. His careful manipulation of tempo—marked by subtle accelerations and decelerations—imbues the symphony with a unique vitality. The third movement, with its skittering strings, bursts forth with a youthful exuberance that is infectious. This performance stands apart from other recordings, such as Rozhdestvensky’s and Verbitsky’s, which, while commendable, lack the visceral punch and orchestral cohesion that Monteux achieves. The recording quality is excellent, capturing the intricate textures of the orchestra with clarity, even if the balance between the various sections occasionally favors the strings at the expense of overall depth.

This two-CD set presents a vibrant snapshot of Tchaikovsky’s genius as interpreted through Monteux’s artistic lens. The recording not only serves as a testament to the high-caliber musicianship of the London Symphony Orchestra but also underscores Monteux’s interpretative genius. The resurgence of these tapes, lost for decades, is a gift to both the scholarly community and the general listener, shedding light on a crucial moment in the history of Tchaikovsky performance. This release deserves a place in the collections of anyone who seeks to understand the depth of Tchaikovsky’s emotional landscape and the interpretative possibilities his works afford. Monteux’s artistry, alongside Ogdon’s electrifying piano, creates a listening experience that resonates with both beauty and emotional intensity, affirming the enduring power of Tchaikovsky’s music.