Composer: Robert Schumann

Composer: Robert Schumann

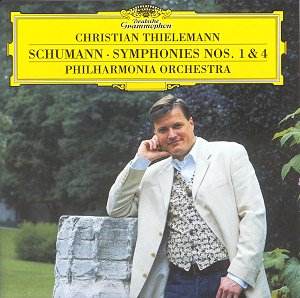

Works: Symphony No. 1 in B flat, Op. 38 – “Spring”; Symphony No. 4 in D minor, Op. 120

Performers: Philharmonia Orchestra, Christian Thielemann, conductor

Recording: February 2001, All Hallows Church, London

Label: Deutsche Grammophon 469 700-2

Robert Schumann’s symphonic oeuvre, marked by its emotional depth and innovative structures, stands as a crucial pillar of the Romantic repertoire. His first symphony, composed in a burst of inspiration during the spring of 1841, is often celebrated for its exuberance, capturing the essence of new beginnings. Conversely, the Fourth Symphony, revised in 1851, reflects a more introspective and complex character, embodying a synthesis of Schumann’s earlier themes and a more mature orchestral language. Together, these works encapsulate the duality of Schumann’s artistic spirit, oscillating between exuberance and introspection, joy and melancholy.

Christian Thielemann’s interpretation of these symphonies, recorded with the Philharmonia Orchestra, presents a compelling exploration of Schumann’s intentions, albeit with notable interpretive choices that evoke a spectrum of responses. The “Spring” Symphony opens with a buoyant theme that Thielemann takes with a deliberate pace, allowing the lush orchestration to unfold organically. The orchestra responds with a warmth that is both engaging and expansive, though one might argue that the tempo occasionally undermines the inherent vitality of the music. The transition to the second theme, marked by a subtle rubato, showcases Thielemann’s ability to shape phrases thoughtfully, yet at times, his insistence on elongation reduces the forward momentum that is critical to the symphonic narrative.

In the Fourth Symphony, Thielemann’s approach is, perhaps, even more controversial. Echoes of Furtwängler’s legendary interpretations are palpable, particularly in the expansive opening motto. The conductor’s use of an extended upbeat before the orchestral crash is a striking homage, yet it raises questions about interpretive originality. While the orchestra’s cohesion and responsiveness to Thielemann’s directions are commendable, the performance risks becoming an echo rather than a fresh interpretation. The ebb and flow of tempo are executed with finesse, but they may sacrifice the tension that Furtwängler so masterfully maintained, leaving moments feeling less urgent than intended.

The recording quality itself is superb, allowing for a rich, detailed soundscape that captures the orchestra’s nuances. The engineering honors the vibrancy of the strings and the resonant clarity of the woodwinds, creating a listening experience that feels immersive. However, the very clarity of the sound can at times highlight the interpretive choices that may not align with Schumann’s more tempestuous spirit. The Scherzo, marked “Molto vivace,” emerges as a particularly sluggish interpretation, which, despite careful phrasing, seems to dull the sparkle of Schumann’s rhythmic intricacies. Similarly, the Finale lacks the exhilarating drive that one might expect, leaving the listener yearning for a more robust conclusion to the symphonic journey.

Thielemann’s readings, while technically astute and emotionally resonant, often tread familiar paths laid by predecessors like Furtwängler, rather than charting new territory in Schumann’s complex emotional landscape. The historical context of these symphonies—reflecting both the exuberance of youth and the weight of experience—demands a performance that captures their dynamic range. While this recording offers a commendable interpretation, it ultimately does not transcend the legacies of its forebears. For those seeking a vivid, innovative exploration of Schumann’s symphonic world, alternative interpretations by conductors such as Sawallisch or Szell may offer a more invigorating experience, unearthing the layered intricacies of Schumann’s genius.

Thielemann’s performance, while polished and executed with admirable orchestral discipline, feels somewhat restrained in its emotional breadth, leaving one to ponder whether it fully encapsulates the essence of Schumann’s symphonic vision.