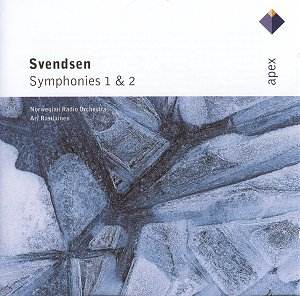

Composer: Johan Severin Svendsen (1840-1911)

Composer: Johan Severin Svendsen (1840-1911)

Works: Symphony No. 1, Op. 4 (1865-6), Symphony No. 2, Op. 15 (1876), Polonaise No. 2, Op. 28 (1881)

Performers: Danish National Radio Symphony Orchestra, Thomas Dausgaard (conductor)

Recorded: August 16-18 and 22-24, 2000, Danish Radio Concert Hall, Copenhagen

Label: Chandos CHAN 9932

Duration: [75.25]

In the pantheon of Scandinavian symphonic composition, Johan Svendsen occupies a somewhat paradoxical position; often overshadowed by the more luminous figures of Grieg and Nielsen, he nevertheless emerges as a captivating voice within the symphonic repertoire. The recent release by Chandos of Svendsen’s first two symphonies alongside the Polonaise No. 2, as interpreted by the Danish National Radio Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Thomas Dausgaard, serves as an insightful exploration into the historical and musical significance of these works.

Svendsen’s Symphony No. 1, composed between 1865 and 1866, arrives in a milieu where the symphonic form was in a state of flux. The echoes of Mendelssohn and Schumann linger, yet the burgeoning Romanticism heralded by the likes of Liszt and Wagner complicates the landscape. As Dyer astutely contextualizes, Svendsen’s first effort is a confident declaration of intent, emerging from the shadow of his contemporaries, particularly Grieg, who heralded it as a triumph for Norwegian music.

The first movement of Symphony No. 1, marked Allegro, showcases Svendsen’s adeptness at thematic development. The initial subject, vigorous and propulsive, is juxtaposed against a more lyrical second theme. This duality is where Svendsen’s artistry shines; however, it is here that one notes a tendency for the lyrical material to feel somewhat underdeveloped. Dausgaard and the orchestra deftly navigate this terrain, emphasizing the contrasting motifs while ensuring that the orchestral fabric remains rich and cohesive. The diminuendo leading to the recapitulation, a moment of exquisite introspection, offers a hint of Svendsen’s ability to infuse drama into traditional structural forms.

The slow movement, Andante, is particularly noteworthy for its expansive paragraphs and lush orchestration. Dausgaard’s interpretation breathes life into this section, allowing the music to unfold with a natural ease that captivates the listener. The movement’s harmonic movement is supported by a tapestry of orchestral tone-painting, revealing Svendsen’s gift for color and atmosphere. This segment stands in stark contrast to Grieg’s own symphonic foray, which, while ambitious, lacks the same level of emotional depth and clarity.

Turning to Symphony No. 2, composed a decade later, one discerns a maturation in Svendsen’s compositional voice. The increased breadth is evident from the outset, with the first movement adopting a more ambitious architecture. The development section offers a wealth of ear-catching motifs, and Dausgaard’s pacing allows these ideas to resonate fully. The second movement, a charming Allegro, is imbued with a delightful buoyancy that showcases the orchestra’s playful character. Here, the strings are particularly adept, their articulation crisp yet warm.

The finale of the second symphony is imbued with a buoyant optimism that encapsulates Svendsen’s ability to craft engaging thematic material. While it may not aspire to the heights of symphonic greatness, it nonetheless provides a satisfying conclusion that is enhanced by the orchestra’s spirited execution. Dausgaard’s conducting style, characterized by kinetic energy and rhythmic precision, serves the music well, ensuring that each movement is animated yet anchored in structural integrity.

The inclusion of the Polonaise No. 2 serves as a delightful interlude, offering a glimpse into Svendsen’s flair for the dance, a facet often overlooked in his larger orchestral works. This piece is executed with a vivacity that evokes the essence of the dance form, presenting a lively contrast to the more serious nature of the symphonies.

In terms of recording quality, the Chandos production is exemplary. The engineering captures the full-bodied sound of the orchestra without sacrificing clarity, allowing each instrument to be heard distinctly, a feat particularly notable in the densely orchestrated passages. The acoustic of the Danish Radio Concert Hall has been well utilized, contributing to a rich, immersive listening experience.

In conclusion, while Svendsen’s symphonies may not ascend to the pantheon of symphonic masterpieces, they undeniably represent a crucial chapter in the narrative of Scandinavian orchestral music. Dausgaard and the Danish National Radio Symphony Orchestra breathe life into these works, revealing their charm and sophistication. This recording serves as a vital reminder of Svendsen’s contributions, inviting listeners to engage with a composer who, though often relegated to the margins of history, provides a bridge between the classical and the modern symphonic idiom. Thus, this release is not merely an archival endeavor but a spirited affirmation of Svendsen’s rightful place within the symphonic tradition.