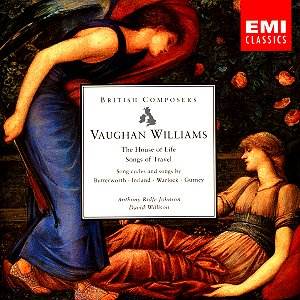

Composer: Ralph Vaughan Williams

Composer: Ralph Vaughan Williams

Works: The House of Life, Songs of Travel

Performers: Anthony Rolfe Johnson (tenor), David Willison (piano)

Recording: 1974, Hornsey Town Hall (RVW), 1975, Assembly Hall, Northwood College (others)

Label: EMI

Ralph Vaughan Williams occupies a seminal place in the English choral and song repertoire, melding the folk traditions of his native land with a distinctively personal harmonic language. His works often reflect a deep engagement with the natural world and the complexities of human emotion, as manifested in the song cycles “The House of Life” and “Songs of Travel.” The former, set to the poetry of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, evokes themes of love, loss, and the transience of beauty, while the latter draws from Robert Louis Stevenson, capturing the spirit of wanderlust and existential reflection. This recording featuring tenor Anthony Rolfe Johnson and pianist David Willison offers a window into these rich landscapes, yet it raises questions about interpretative choices that may not align with the composer’s intent.

Johnson’s approach is marked by a careful enunciation and a deliberate pacing that, while aiming for clarity, often results in a performance that feels overly measured. His interpretation of the cycle “Songs of Travel” stretches the phrases, giving the impression of a singer searching for meaning amidst the text rather than a fully engaged storyteller. The opening “The Vagabond” lacks the rhythmic impulsion that propels the narrative forward, resulting in an interpretation that feels more like a recitation than a passionate declaration. The piano accompaniment, handled adeptly by Willison, provides a rich harmonic backdrop, but the overall dynamic interplay is sometimes overshadowed by Johnson’s cautious delivery.

In “The House of Life,” the subtle nuances of Vaughan Williams’ harmonic language are not fully explored. For instance, in “Love’s Minstrels,” the climactic moments lack the required dramatic intensity, rendering the poignant text somewhat limp. While Johnson’s falsetto passages may be intended to convey a sense of fragility, they often verge on the overly mannered, detracting from the emotional weight of the poetry. The final lines of “Death in Love,” intended to resonate with a haunting finality, instead register as a mere whisper, lacking the gravitas that the music demands.

The recording quality, typical of EMI’s 1970s output, is generally satisfactory, capturing the warmth of the piano and the clarity of Johnson’s voice, though it does not escape the era’s constraints in dynamic range and spatial detail. The engineering provides a somewhat intimate setting, yet it does not quite convey the full breadth of the vocal and instrumental colors that can be found in more modern interpretations.

Comparative listening reveals that the interpretation by Johnson and Willison lacks the visceral impact of recordings by artists such as John Shirley-Quirk, whose readings of these cycles bring forth an urgency that Johnson’s approach often circumvents. Shirley-Quirk’s ability to navigate the emotional landscape of Vaughan Williams with both finesse and vigor infuses the music with a life that feels absent here. While Rolfe Johnson’s technique is commendable, the overall effect is that of a performance that, though earnest, does not penetrate the depths of the works’ profound emotional and musical implications.

The recording serves as a historical artifact that may resonate with those who cherish the early interpretations of British song repertoire, yet it ultimately falls short of illuminating the true essence of Vaughan Williams’ artistry. While it may provide an interesting point of reference for listeners familiarizing themselves with the composer’s vocal works, it does not replace the more compelling and nuanced performances available today. The collection’s value lies more in its nostalgic appeal than in its artistic achievements, revealing a performance that is more about the preservation of a tradition than its vigorous reimagining.