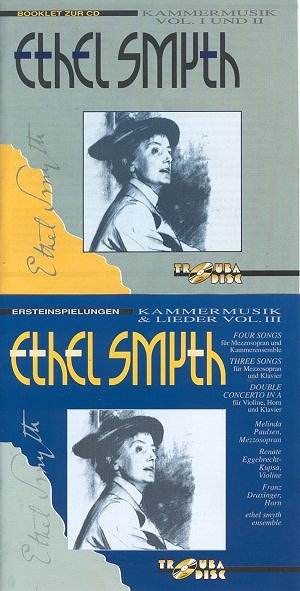

Composer: Ethel Smyth

Composer: Ethel Smyth

Works: Violin Sonata Op. 7 (1887), String Quintet Op. 1 (1883), Cello Sonata Op. 5 (1887), String Quartet in E Minor (1902, 1912), Four Songs for Mezzo and Chamber Ensemble (1907), Three Songs for Mezzo and Piano (1913), Double Concerto for Violin, Horn, and Piano (1926), Five Lieder Op. 4 (1877), Cello Sonata in C Minor (1880), Three Moods of the Sea for Baritone and Piano (1913)

Performers: Renate Eggebrecht-Kupsa (violin), Friedemann Kupsa (cello), Céline Dutilly (piano), Melinda Paulsen (mezzo), Ulrike Siebler (flute), Georgi Georgiev (viola), Corinna Zirkelbach (harp), Franz Draxinger (horn), Maarten Koningsberger (baritone)

Recording: Various dates between 1990 and 1997, Bauer Studios, Ludwigsburg, Germany

Label: Troubadisc

Ethel Smyth, a figure often overshadowed in the annals of classical music, emerges compellingly in this extensive four-volume collection from Troubadisc. As a pioneering female composer who defied societal norms in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Smyth’s oeuvre is replete with rich thematic material that mirrors her struggles and triumphs as both an artist and a suffragette. These recordings not only illuminate her significant contributions to chamber music and song but also reflect the evolving trajectory of her style, from Brahmsian influences to a more modern expressionist language.

The performances throughout these volumes are marked by a commendable mix of technical proficiency and interpretative insight. Renate Eggebrecht-Kupsa’s rendering of the Violin Sonata Op. 7 reveals a warm fantasy that evokes the spirit of Brahms while simultaneously engaging with Dvořák’s introspection. The third movement, aptly titled “Romance,” embodies a hiccuping liberation reminiscent of Dvořák’s American Quartet. This ability to navigate between emotive lyricism and rigorous structure is a testament to Smyth’s compositional prowess. The String Quintet Op. 1, performed with buoyancy and clarity, presents a delightful interplay of voices, with the lush textures and pastoral themes suggesting echoes of Mendelssohn and a youthful exuberance that belies its early date of composition.

The Cello Sonata Op. 5 stands out as particularly virile and commanding, showcasing Friedemann Kupsa’s vibrant playing. His adagio non troppo is a highlight, revealing a deeply expressive heart that resonates with the listener. The recording quality here is especially noteworthy; the engineering captures the cello’s resonance beautifully, while the piano accompaniment by Dutilly complements with an unobtrusive yet supportive presence. The technical sound quality across all volumes is excellent, with a clean, balanced mix that allows each instrument to be heard distinctly without overwhelming the others.

Volume 3 introduces a fascinating shift in Smyth’s stylistic approach with her Four Songs for Mezzo and Chamber Ensemble, which evoke a vivid atmosphere through the use of harp and flute. Melinda Paulsen’s warm voice navigates the intricacies of Smyth’s lyrical language, offering a rich interpretation that highlights the emotional depth of the texts. The songs, particularly “La Danse,” intertwine the harmonic language of Berlioz and Chausson, and her performance rises to meet the challenge of Smyth’s innovative textures, revealing a composer who was unafraid to explore the avant-garde.

The final volume showcases Smyth’s later works, including the Cello Sonata in C Minor and the Three Moods of the Sea. Here, Maarten Koningsberger’s baritone performance brings a robust expressiveness, particularly in the latter work, where the fractured tonality reflects the emotional turmoil of the era. This volume also features the Double Concerto, which is given a chamber music treatment that emphasizes the emotional core of the piece, allowing for a more intimate experience than orchestral renditions.

The historical context of Smyth’s works cannot be overlooked. Emerging from the shadow of her male contemporaries, her music reflects the aspirations and challenges of a woman striving for recognition in a male-dominated field. The thematic consistency across her oeuvre, particularly her engagement with societal issues, is not merely incidental but integral to her identity as a composer. The inclusion of works written during her suffragette activism, such as the militant “On the Road,” reminds us of the intertwining of her personal and artistic lives.

Smyth’s music, often dismissed as derivative, reveals a more nuanced character upon closer examination. These recordings challenge the notion that her style is merely an echo of Brahms or Dvořák. Instead, they affirm her place as a vital voice in the evolution of 20th-century music. The Troubadisc series serves not only as a revival of Smyth’s works but also as a critical reassessment of her legacy, underscoring the importance of her contributions to the canon of classical music. As such, the collection is an invaluable resource for both enthusiasts and scholars alike, offering a comprehensive look at an artist whose time has come to be celebrated anew.