Composer: Jean Sibelius

Composer: Jean Sibelius

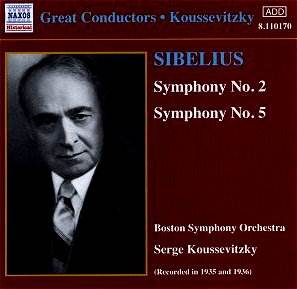

Works: Symphony No. 2 (1902), Symphony No. 5 (1917)

Performers: Boston Symphony Orchestra, Serge Koussevitsky, conductor

Recording: Symphony Hall, Boston, 24 Jan 1935 (No. 2), 29 Dec 1936 (No. 5)

Label: NAXOS HISTORICAL 8.110170

Sibelius’s symphonic oeuvre stands as a testament to the Finnish composer’s profound engagement with nature and nationalism, with his Second and Fifth Symphonies serving as pivotal examples of his evolving musical language. The Second Symphony, composed in 1902 amidst a backdrop of burgeoning Finnish identity, encapsulates a struggle between light and darkness, while the Fifth Symphony, finalized in 1917, reflects a more concentrated and expansive vision, marking a significant evolution in his style. This particular release from Naxos, featuring historical recordings conducted by Serge Koussevitsky, an ardent advocate for Sibelius’s music, offers a window into early interpretations that resonate with both historical significance and interpretative inquiry.

Koussevitsky’s approach to the Second Symphony is marked by a broadness of tempo that, while characteristically grand, sometimes sacrifices the tautness that the work demands. The expansive pacing may appeal to those who appreciate a leisurely traversal of Sibelius’s landscapes; however, it risks undermining the inherent tension, particularly in the finale. The Boston Symphony’s string section shines in moments of lyrical clarity, especially in the third and fourth movements where their clean articulation enhances the symphonic narrative. Yet, the excessive deliberation in the finale feels less cohesive, lacking the whip-crack energy that conductors like Beecham and Barbirolli achieve, leaving listeners longing for a more compelling drive through the climactic passages.

In contrast, the recording of the Fifth Symphony reveals a slight refinement in Koussevitsky’s interpretative choices, where the orchestral textures possess a richness that is commendable. The initial movement showcases a master-builder at work, with Koussevitsky’s handling of the heroic tolling statements at 7:14 embodying a structural clarity that is striking. Here, the tension is palpable, particularly at 5:58, where the icy whispers of the strings convey a haunting urgency. However, the pacing still tilts towards the expansive; the second movement’s four-square tempo lacks the vitality found in more incisive performances. The brass interjections, while powerful, do not carry the mordant grip present in more dynamic accounts, leaving a sense of missed opportunity in achieving the movement’s full potential.

The technical quality of these historical recordings, restored by Mark Obert-Thorn, merits attention. While some background noise persists, it is judiciously managed to maintain an immediacy that allows the listener to appreciate the nuances of Koussevitsky’s orchestration. The documentation accompanying the Naxos release is exemplary, providing context and provenance that enrich the listening experience. Compared to the Pearl set from 1990, this Naxos transfer offers a clearer soundscape, with the spectral remnants of surface noise effectively subdued, ensuring that the focus remains on the music itself.

Assessing these performances ultimately reveals a duality. While Koussevitsky’s interpretations of Sibelius’s Second and Fifth Symphonies present a formidable yet occasionally flawed vision, they remain historically significant. The blend of expansive tempi and rich orchestral sonority creates a listening experience that, despite its shortcomings, invites reflection on the evolution of Sibelius’s symphonic artistry. This release serves not only as an archive of Koussevitsky’s legacy but also as a reminder of the interpretative challenges intrinsic to Sibelius’s music, making it a worthwhile addition for those interested in the composer’s complex identity within the symphonic tradition.