Jean SIBELIUS (1865-1957)

Jean SIBELIUS (1865-1957)

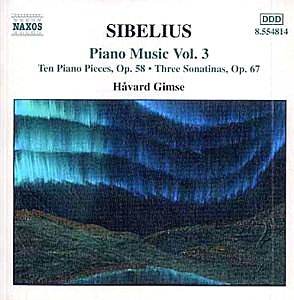

Piano Music, Vol. 3: 10 Pieces, Op. 58; 3 Sonatinas, Op. 67; 2 Rondinos, Op. 68

Havard Gimse (pianoforte)

NAXOS 8.554814 [60.32]

Recorded in St. Martin’s Church, East Woodhay, Hampshire, 25.11.1999 and 23.11.2000

In this third volume of Jean Sibelius’s piano music, pianist Havard Gimse confronts a repertoire often relegated to the periphery of the composer’s illustrious output. Frequently dismissed as mere salon pieces, the selections in this collection unveil a nuanced landscape of emotional depth and technical exploration, challenging preconceived notions of Sibelius as solely a master of symphonic form.

Sibelius’s piano works have historically suffered from a lack of attention, with critics often viewing them as trifles or commercial expedients to support his more substantial orchestral ambitions. However, Gimse’s interpretations compel us to reconsider these pieces, elevating them through a thoughtful and engaging performance that invites listeners to explore the rich, if understated, world of Sibelius’s keyboard writing.

The disc opens with “Rêverie,” Op. 58, a piece that imbues the listener with an impressionistic texture, albeit one that avoids the lush harmonic language typical of Debussy and Ravel. Instead, Gimse’s interpretation evokes the ethereal quality found in some of Scriabin’s more introspective works, yet retains a Nordic clarity that is distinctly Sibelius. The delicate balance of light and shadow in this piece is articulated through Gimse’s deft touch, revealing a surface simplicity that belies the work’s underlying emotional complexity.

In the “Sonatinas,” particularly the first movement of the first Sonatina, Op. 67, Gimse exhibits a commendable grasp of the structural integrity of the work while also allowing for moments of expressive freedom. The way he navigates the interplay between melody and accompaniment is especially commendable; here, the pianist manages to maintain a singing line that resonates with both poignancy and vigor. The contrasts between the angular motifs and lyrical passages are rendered with clarity, a testament to Gimse’s deep understanding of Sibelius’s harmonic language, which often hints at a broader orchestral palette without ever fully adopting it.

The two Rondinos, Op. 68, offer further insight into Sibelius’s stylistic range. The contrasting character of each piece provides Gimse with opportunities to showcase his interpretive versatility. The first, marked by a buoyant, dance-like quality, comes alive under Gimse’s fingers, while the second delves into a more reflective mood. Here, Gimse’s ability to sustain a delicate line against a backdrop of harmonic richness is particularly effective, allowing the music to breathe and resonate within the acoustic of St. Martin’s Church, which, despite its somewhat stark recording qualities, provides an intimate setting that serves the repertoire well.

Gimse’s performance choices are bold yet considered; he employs rubato judiciously, breathing life into phrases without succumbing to excessive sentimentality. This is especially evident in “In the Evening,” where the nuances of tempo and dynamic shading create a haunting atmosphere. While some may argue that the piece lacks a conventional singing tone, Gimse’s interpretation aligns with Sibelius’s own aesthetic, which often prioritizes emotional truth over melodic ease.

Historically, Sibelius’s forays into piano composition reflect his broader quest for a national musical identity, distinct from the established norms of Western European music. The absence of the more frequently acknowledged figures like Grieg is notable; instead, Sibelius seems to find inspiration in a more personal, introspective realm, crafting music that resonates with the Finnish landscape and spirit. Gimse’s exploration of these works not only illuminates their intrinsic value but also situates them within the context of Sibelius’s overarching artistic narrative.

The engineering of this recording, while occasionally revealing the limitations of the church’s acoustic, ultimately serves the music well. The clarity of Gimse’s touch and the resonant qualities of the instrument are well captured, allowing the listener to appreciate the subtleties of the textures and the interplay of thematic material.

In conclusion, Havard Gimse’s interpretation of Sibelius’s piano music in this volume is a revelation. It not only affirms the composer’s worth beyond the orchestral domain but also challenges us to reconsider the depth and significance of his piano writing. This disc is an essential listen for those willing to broaden their understanding of Sibelius, and it stands as a testament to the potential for rediscovery within the classical canon. As I reflect on this recording, I find myself not only surprised but grateful for Gimse’s artistry, which has encouraged me—and perhaps others—to revisit these works with fresh eyes and ears.