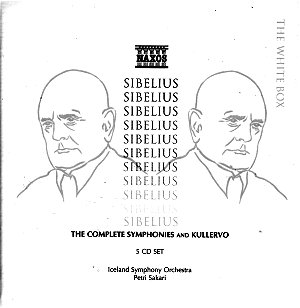

Composer: Jean Sibelius

Composer: Jean Sibelius

Works: The Complete Symphonies, Symphony No. 1 (1899), Symphony No. 2 (1902), Symphony No. 3 (1907), Symphony No. 4 (1911), Symphony No. 5 (1919), Symphony No. 6 (1923), Symphony No. 7 (1924), Kullervo Symphony (1899), Tempest Suite No. 1 (1925), Tempest Suite No. 2 (1925)

Performers: Iceland Symphony Orchestra, Petri Sakari (apart from Kullervo), Johanna Rusanen (soprano), Esa Ruutunen (baritone), Laulun Ystavet Male Choir, Turku Philharmonic Orchestra, Jorma Panula (Kullervo)

Recording: Symphonies 1-3 (Nov 1996 – Feb 1997), Symphonies 4-7 (Nov 1997 – Mar 2000), Kullervo (June 1996), all recorded in Iceland

Label: NAXOS

Jean Sibelius, the quintessential voice of Finnish nationalism in music, has long held a distinctive place in the symphonic repertoire. His symphonies encapsulate a journey through a landscape of emotional depth and national identity, drawing from the stark beauty of his homeland. The Naxos White Box collection of Sibelius’s complete symphonies, conducted by Petri Sakari, presents an opportunity to reassess these monumental works through a fresh lens, emphasizing both the historical significance and the evolving interpretations of Sibelius’s music.

Sakari’s interpretation of the First Symphony is marked by a reflective restraint, eschewing the more bombastic tendencies often favored in earlier renditions. This measured approach allows for a nuanced appreciation of the symphony’s intricate textures, particularly evident in the second movement, where the conductor’s sensitivity facilitates a dialogue between the strings and woodwinds. The recording, however, presents challenges; the initial hushed strings of the opening bars are almost inaudible, necessitating adjustments in volume that disrupt the listening experience. This contrasts sharply with the vivid soundscape Sakari achieves in the Third Symphony, where a more immediate microphone placement captures the invigorating rhythmic energy of the orchestra, revealing the symphony as an unheralded gem that deserves greater recognition.

The engineering choices across the collection reflect a commendable ambition to recreate a natural concert hall balance, though results vary significantly. The Fourth Symphony, with its stark and brooding character, emerges powerfully in this context, as Sakari harnesses the orchestral forces to evoke a chilling landscape, underscored by the icy quality of the Iceland Symphony Orchestra’s sound. This contrasts with the Fifth Symphony, where the exuberance of the “swan hymn” is realized in a manner that is both grand and transparent, capturing the essence of Sibelius’s vision while avoiding excessive sentimentality.

Sibelius’s Kullervo, a monumental work that intertwines orchestral and choral elements, is treated with gravitas under Jorma Panula’s direction. The soloists, Rusanen and Ruutunen, bring a fervent intensity to their roles, supported by the robust sound of the Laulun Ystavet Male Choir. The recording achieves a visceral impact, yet it is worth noting that it remains overshadowed by the benchmark set by Berglund’s classic EMI recording. Nevertheless, Panula’s interpretation shines in its ability to convey the work’s dramatic arc, particularly in the climactic moments where choral forces intertwine with orchestral might.

The Tempest Suites, often regarded as lighter fare, are handled with a grace that belies their complexity. Sakari manages to imbue the music with a sense of effortless elegance, particularly in Suite No. 1, which encapsulates the storm’s tumult and subsequent calm. This lighter texture provides a refreshing contrast to the more substantial symphonic works, serving as delightful interludes that highlight Sibelius’s versatility.

Naxos’s White Box series, encapsulated in a clean, understated design, resonates with the same integrity that characterizes Sakari’s conducting. The inclusion of bilingual texts for Kullervo demonstrates a commitment to accessibility, a hallmark of Naxos’s approach that enhances the listener’s engagement with the music. Ultimately, this set offers an engaging exploration of Sibelius’s symphonic landscape, even if it occasionally falters in the engineering department. The performances, while distinct and thoughtful, may not entirely eclipse the historical giants of the repertoire, yet they contribute meaningfully to the ongoing dialogue surrounding Sibelius’s legacy. This collection is a worthy addition for those seeking both familiarity and fresh perspectives on a composer whose music continues to resonate deeply within the fabric of classical music.