Dmitri SHOSTAKOVICH (1905-1975)

Dmitri SHOSTAKOVICH (1905-1975)

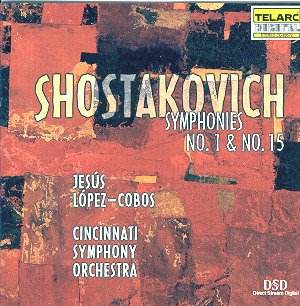

Symphony No. 1 in F minor, Op. 10

Symphony No. 15 in A, Op. 141

Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra conducted by Jesus Lopez-Cobos

Rec Music Hall, Cincinnati, Ohio, September 24-25, 2000

TELARC CD-80572 [76.57]

The coupling of Shostakovich’s First and Fifteenth Symphonies offers a compelling juxtaposition of youthful exuberance and reflective somberness, a thematic arc that is both poignant and revealing within the context of the composer’s life. Each piece serves as a distinctive lens through which we may examine the evolution of Shostakovich’s musical language, and yet, the interpretation by Jesus Lopez-Cobos, despite its meticulous preparation, ultimately lacks the depth and nuance that these monumental works demand.

Shostakovich composed his First Symphony at the precocious age of nineteen, an audacious debut that heralds the arrival of a singular artistic voice. The work bursts forth with vibrant energy, characterized by its innovative use of counterpoint and motivic development. Lopez-Cobos’s reading, while competent, does not fully seize the youthful buoyancy and sardonic wit present in the Scherzo, which should crackle with an almost frenetic chase-like intensity. Instead, it feels somewhat subdued, lacking a visceral edge that would propel the listener into the exhilarating chaos of youth.

In contrast, the Fifteenth Symphony, composed in 1971, is a profound reflection on mortality and the existential weight of memory. The orchestration is both sparse and vivid, deftly employing chamber-like textures that convey a haunting introspection. However, Lopez-Cobos fails to unveil the deeper emotional undercurrents that lie beneath the score. The opening movement, traditionally an arresting statement of intent, here emerges as oddly unremarkable, lacking the requisite gravitas and tension. The notorious single stroke of the side drum at the climax, intended to evoke a jarring severance, is rendered disappointingly innocuous. This moment, pivotal in its potential to resonate with the audience as a symbol of finality, instead dissipates without the dramatic punch that Shostakovich intended.

Lopez-Cobos’s interpretive choices seem to lean towards a neutral stance; while his orchestra, undoubtedly virtuosic, executes each note with precision, the performance lacks the emotional bite that characterizes the best interpretations of these symphonies. The slow movement, typically imbued with a profound sense of solitude, fails to evoke the shivering loneliness one might expect, despite a well-executed cello solo that hints at deeper feelings yet does not fully realize them.

The engineering of the Telarc recording is, as always, of high quality, with a clarity that allows the listener to appreciate the intricate textures of Shostakovich’s orchestrations. Yet, without a corresponding interpretive vision, the sonic clarity becomes a double-edged sword; it illuminates the music’s surface while leaving its emotional core in shadow.

In considering alternative recordings, the listener might find greater depth in the interpretations of conductors such as Kurt Sanderling or Mariss Jansons, whose commitment to the emotional intricacies of Shostakovich’s music invites a more profound engagement with the text. Sanderling’s readings, in particular, provide a riveting sense of narrative drive and emotional turbulence that Lopez-Cobos’s interpretation lacks.

This release may serve as an introductory gateway for those unfamiliar with Shostakovich’s symphonic output, offering a clear, if somewhat flat, exposition of the notes. However, for seasoned listeners, the interpretive shortcomings may lead to a sense of dissatisfaction, for the music remains uncharacteristically subdued in the hands of Lopez-Cobos.

In conclusion, while the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra under Jesus Lopez-Cobos delivers a technically proficient and polished performance of Shostakovich’s First and Fifteenth Symphonies, the lack of interpretive depth ultimately undermines the emotional gravity of these works. The inherent greatness of the symphonies persists, of course, but one must seek out performances that dare to engage with the complexities of Shostakovich’s narrative—performances that reveal not only the music but the man behind it, grappling with the specter of his own history.