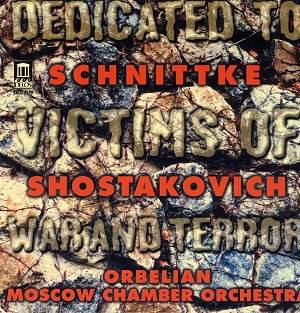

Composer: Dmitri Shostakovich

Composer: Dmitri Shostakovich

Works: Chamber Symphony Op. 110a; Alfred Schnittke: Concerto for Piano and Strings

Performers: Moscow Chamber Orchestra; Constantine Orbelian, piano

Recording: Skywalker Sound, Marin County, California, 5 & 7 March 2000

Label: Delos DE 3259

Dmitri Shostakovich’s Chamber Symphony, Op. 110a, serves as a poignant testament to the composer’s complex relationship with his art and the oppressive political landscape of his time. This work is a transcription of his Eighth String Quartet, famously imbued with a sense of personal reflection and despair, which Shostakovich composed during a period of intense turmoil in his life. The Eighth Quartet, filled with self-referential motifs, draws heavily from earlier works, creating a tapestry of nostalgia and sorrow that resonates deeply within the listener. In contrast, Alfred Schnittke’s Concerto for Piano and Strings presents a different, yet equally compelling, narrative, marked by innovative compositional techniques and an exploration of the boundaries of tonality.

Constantine Orbelian’s interpretation of Shostakovich’s Chamber Symphony, while ambitious, encounters significant challenges. The orchestration, expanded from the original string quartet, tends to dilute the sharpness of the work’s emotional core. The Moscow Chamber Orchestra, while capable, often underplays the essential accents that lend Shostakovich’s music its characteristic intensity. For instance, in the long-breathed first violin melodies that should evoke a profound sense of desolation, the massed strings create a cushion that softens the harsh realities embedded in the music. The fourth movement, a Largo, emerges as the standout segment, where Orbelian’s control over dynamics effectively maintains the tension between silence and sound, yet this moment of clarity cannot fully redeem an interpretation that feels at times overblown and lacking in the requisite bite.

The performance of Schnittke’s Concerto for Piano and Strings showcases Orbelian’s strengths more effectively, revealing a nuanced understanding of the composer’s intentions. The opening movement’s Chopinesque motifs benefit from Orbelian’s sensitive touch, where the interplay between the piano and strings captures the delicate balance of melancholy and irony characteristic of Schnittke’s style. The third movement, labeled ‘Tempo di valse’, is particularly striking; its relentless, dark energy unfolds with a cumulative power that is both unsettling and compelling. Here, Orbelian’s interpretation shines, illustrating the complex relationship between rhythm and expression that Schnittke masterfully weaves throughout the work.

Recording quality is generally acceptable, though the proximity of the microphones occasionally brings an uncomfortable intimacy that detracts from the orchestral blending. The engineering choices create a soundstage that, while clear, feels overly close, which may not do justice to the expansive emotional landscape Shostakovich and Schnittke both intended to convey. In comparison to notable recordings, such as those featuring the Borodin String Quartet or the acclaimed performances by other pianists like András Schiff, this disc falls short in both interpretative depth and sonic balance.

A decisive assessment reveals that while the coupling of Shostakovich’s Chamber Symphony and Schnittke’s Concerto for Piano and Strings is conceptually sound, the execution falters significantly. Orbelian’s interpretations, while occasionally illuminating, lack the necessary intensity and precision to fully engage with the complexities of the scores. The recording, though competent, does not elevate the performance to a level that would compel repeated listening, leaving listeners with a sense of unfulfilled potential rather than the profound impact these works can achieve.