Composer: Franz Schubert

Composer: Franz Schubert

Works: Schwanengesang, D. 957; Johannes Brahms, Vier ernste Gesänge, op. 121

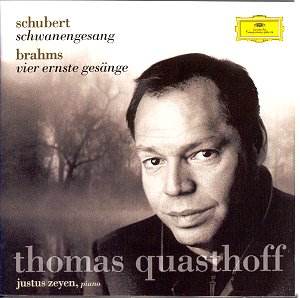

Performers: Thomas Quasthoff (baritone), Justus Zeyen (pianoforte)

Recording: Recorded in the Bavaria Musikstudios, Munich, December 2000

Label: Deutsche Grammophon (DG 471 030-2)

Franz Schubert’s “Schwanengesang,” composed in the twilight of his life, represents a profound summation of his art, despite the publisher’s somewhat misleading title, which obscures the work’s composite nature. The collection comprises a selection of songs set to texts by Rellstab and Heine, interspersed with the standalone “Die Taubenpost,” a final flourish that provides a bittersweet contrast to the emotional depth of the preceding pieces. While not a unified cycle in the narrative sense, the thematic relationship between longing and existential reflection connects these works, marking a significant evolution in Schubert’s output. This recording juxtaposes Schubert’s late lyricism with Brahms’s “Vier ernste Gesänge,” a meditation on mortality and the divine, illustrating the enduring resonance of the lied within the German song tradition.

Thomas Quasthoff’s interpretation of Schubert’s songs is marked by a warm, sonorous tone that conveys both vulnerability and strength. While his lower register occasionally lacks the depth one might desire—most notably in “In der Ferne,” where the low A-flat dissipates before its full value—his upper range is more secure, delivering a firm and rounded sound. Quasthoff’s phrasing tends to favor expressiveness, yet moments such as the opening of “Der Doppelgänger” border on excessive pianissimo, rendering the subtleties lost in a concert hall setting. This approach, while artistically valid, risks alienating listeners who might seek the clarity of intention that Schubert’s intricate lines demand.

Justus Zeyen’s pianism, however, raises more substantial concerns. In “Liebesbotschaft,” the demi-semiquavers lack the requisite clarity, betraying a misalignment with Schubert’s transparent textures. Such moments of muddiness are regrettable, particularly when one considers the meticulous detail Schubert imbues within his piano writing. Problems persist in “Kriegers Ahnung,” where Zeyen’s handling of rhythmic accents becomes clumsy, diminishing the melodic line’s expressive potential. The moments of disunity in “Die Stadt” exemplify this, where the middle notes overpower the upper voice, obscuring the delicate balance Schubert’s harmonies necessitate. This inconsistency culminates in a disheartening interpretation of “Ständchen,” where Zeyen’s exaggerated rubato disrupts the essential echoing interplay between voice and piano, reducing what should be an intimate conversation to a display of ostentation.

Brahms’s “Vier ernste Gesänge” showcases Quasthoff’s strengths more effectively, though the gravitas of the texts requires an emotional depth that is occasionally absent. The final song, with its profound biblical references, demands a spiritual resonance that transcends mere technical prowess. While Quasthoff sings with commendable sensitivity, he lacks the transcendent quality found in the interpretations of Kathleen Ferrier, whose ability to convey compassion and depth has set a benchmark for generations.

Recording quality is generally commendable, capturing the nuances of Quasthoff’s voice, though Zeyen’s contributions occasionally falter in clarity, suggesting limitations in the engineering decisions made during the session. The overall sound has a richness that enhances the lyrical qualities of Schubert’s writing but suffers from the imbalance caused by Zeyen’s less-than-ideal execution of the piano parts.

This recording, while featuring moments of lyrical beauty and emotional insight, ultimately falls short of the exalted standards set by historical precedents. Quasthoff’s interpretation resonates with warmth, yet lacks the deeper emotional current that can elevate these songs to their fullest expressive potential. The discrepancies in Zeyen’s playing detract from the overall experience, rendering this particular rendition unremarkable when placed alongside the wealth of exceptional performances available in the lieder canon. For those seeking an entry into Schubert’s and Brahms’s worlds, it would be prudent to explore more established interpretations that capture the essence and complexity of these great composers.