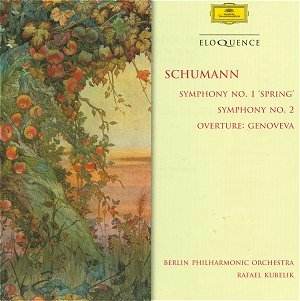

Composer: Robert Schumann

Composer: Robert Schumann

Works: Symphony No. 1 Spring (1841), Symphony No. 2 (1846), Symphony No. 3 Rhenish (1850), Symphony No. 4 (1841), Genoveva Overture (1850), Manfred Overture (1849)

Performers: Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Rafael Kubelik (conductor)

Recording: Berlin, 1963, 1964, stereo, ADD

Label: Deutsche Grammophon Eloquence 463 200-2, 463 201-2

Robert Schumann’s symphonic oeuvre, characterized by its lyrical depth and innovative orchestration, emerges with remarkable clarity and vitality in Rafael Kubelik’s interpretations with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. Composed during a pivotal time in the early Romantic period, Schumann’s four symphonies encapsulate not only his personal struggles but also the broader cultural shifts of the 19th century. The juxtaposition of emotional intensity and formal innovation is a hallmark of Schumann’s style, and Kubelik’s readings shed light on these complexities.

The recording quality of these 1960s analog sessions is particularly noteworthy. The engineers at Deutsche Grammophon have achieved a sound that is both well-contoured and rich, showcasing the Berlin Philharmonic’s characteristic warmth without sacrificing detail. The strings possess a muscular quality, enveloping the listener with a robust yet refined sound, while the brass, especially the French horns, resonate with a noble clarity that enhances the orchestral tapestry. The low hiss typical of analog recordings is commendably minimal, allowing the music’s emotional subtleties to emerge without distraction.

Kubelik’s interpretive choices bring a refreshing perspective to Schumann’s symphonies. In the Spring Symphony, for instance, the opening brass fanfare recalls the dramatic weight of Beethoven’s influence, yet Kubelik artfully balances this with a buoyant forward momentum that embodies the work’s youthful spirit. However, the horns at 1:54 in the finale could have benefitted from greater prominence, a missed opportunity to capitalize on their potential grandeur. The Scherzo of the Second Symphony, with its flickering virtuosity, is particularly exhilarating under Kubelik’s baton, suggesting an urgency that mirrors Schumann’s own restless spirit.

The emotional depth of the Rhenish Symphony is masterfully rendered, especially in the rolling grandeur of its final movement, where Kubelik’s control over the orchestra is evident. His interpretation of the Third Symphony does not shy away from the dramatic, yet it avoids the more frenetic abandon one might associate with other conductors, such as George Szell. Instead, Kubelik opts for a more measured approach, allowing the music’s intricate textures to unfold organically. This is particularly effective in the third movement’s lebhaft section, where the nuanced terracing of dynamics highlights the emotional stakes within the narrative.

The orchestral execution is generally impeccable, although one might find moments where a slightly more aggressive articulation could enhance the dramatic impact. The Manfred Overture, with its tempestuous opening, showcases the orchestra’s virtuosity, particularly in the rapid, slashing lines of the violins at 2:40—a moment that crackles with energy. However, the modest conclusion of the Overture feels somewhat understated, leaving a lingering sense of what might have been had it been placed as the opening track.

Kubelik’s recordings of Schumann’s symphonies, though perhaps overshadowed by modern interpretations, offer a thoughtful and enriching listening experience. The blend of drama and lyricism, coupled with the Berlin Philharmonic’s exceptional musicianship, presents a compelling case for these performances. They resonate with an authenticity that invites both reflection and appreciation, making them recordings to be revisited and cherished. As such, these interpretations stand as a testament to Kubelik’s artistry and Schumann’s indelible impact on the symphonic form.