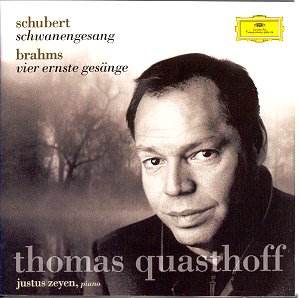

Composer: Franz Schubert

Composer: Franz Schubert

Works: Schwanengesang, D. 957; Johannes Brahms, Vier ernste Gesänge, op. 121

Performers: Thomas Quasthoff (baritone), Justus Zeyen (pianoforte)

Recording: Bavaria Musikstudios, Munich, December 2000

Label: Deutsche Grammophon

The juxtaposition of Schubert’s Schwanengesang and Brahms’ Vier ernste Gesänge forms a profound exploration into the realms of longing, love, and existential reflection, albeit through disparate musical lenses. Schubert, whose life was tragically brief, left a legacy of lieder that extends beyond mere vocal expression into the very fabric of human emotion. The Schwanengesang, published posthumously in 1828, is not a cohesive cycle in the traditional sense, yet it offers an intricate tapestry woven from the poetry of Rellstab and Heine, encapsulating the essence of loss and yearning. In contrast, Brahms, writing nearly seventy years later, grapples with themes of mortality and the human condition in his Vier ernste Gesänge, which reflect a mature artist’s engagement with the deeper philosophical questions of existence.

Quasthoff’s interpretation of Schubert’s works reveals a baritone of commendable warmth and character, yet his execution sometimes falls short of the heartfelt poignancy that these songs demand. For instance, in “In der Ferne,” the low A-flat struggles to maintain its resonance, dissipating before its full duration. Such challenges in the lower register detract from the emotional impact, as Schubert’s lyrical lines often hinge on the singer’s ability to convey sustained beauty. A potential remedy could have been to transpose this piece to a slightly higher key, allowing for a fuller exploration of its emotional depth.

Zeyen’s piano accompaniments, while adequate, occasionally lack the necessary clarity and precision essential to Schubert’s intricate textures. The demi-semiquavers in “Liebesbotschaft” come across muddled, undermining the transparency crucial to conveying Schubert’s delicate interplay between voice and piano. Additionally, Zeyen’s treatment of the rhythmic nuances in “Kriegers Ahnung” results in an ungraceful interpretation that feels more like a bump than a nuanced shading of the music. The staccato chords, intended to articulate the piece’s emotional contours, instead sound cumbersome and harsh.

The final song of Schwanengesang, “Die Taubenpost,” serves as an interesting counterpoint to the preceding Heine settings, offering a lighter, almost whimsical relief. Quasthoff navigates this piece with commendable agility, yet the overall interpretation suffers from Zeyen’s tendency towards excessive rubato, particularly in “Ständchen.” Here, the pianist’s overt expressiveness detracts from the piece’s inherent simplicity and charm, creating a dissonance with the understated elegance of Schubert’s music.

Turning to Brahms, Quasthoff’s interpretation of Vier ernste Gesänge reflects a deeper engagement with the text’s gravitas. The baritone’s voice flourishes in the upper register, and while he occasionally employs a head voice that may seem questionable in a few instances, the overall execution remains compelling. Brahms’ use of biblical texts, particularly the poignant reflections on death and transience, is rendered with a sincerity that resonates deeply. However, the emotional weight of these songs, as famously captured by Kathleen Ferrier, feels somewhat muted in this rendition. Ferrier’s unmatched ability to imbue her performances with a palpable sense of compassion creates a benchmark that Quasthoff, though skilled, does not entirely reach.

Despite the promising elements of Quasthoff’s voice, the recording suffers from some technical deficiencies. The engineering lacks the clarity necessary to fully appreciate the interplay between voice and piano, occasionally relegating the piano to a background role rather than a collaborative partner in the dialogue. The overall sound quality does not match the high standards expected from a Deutsche Grammophon release, leaving listeners yearning for a more cohesive auditory experience.

Quasthoff’s thoughtful approach to the repertoire showcases his potential as a lieder singer, but ultimately, this recording does not ascend to the heights of interpretative greatness. The absence of a deeper emotional connection, particularly in the Schubert works, alongside Zeyen’s uneven pianism, suggests that listeners seeking a definitive interpretation of these masterworks would be better served by exploring the legacies of Fischer-Dieskau or Ferrier. The compelling nature of these songs is undeniable, yet they require performers who can unlock their profound depths, a feat this recording only partially achieves.