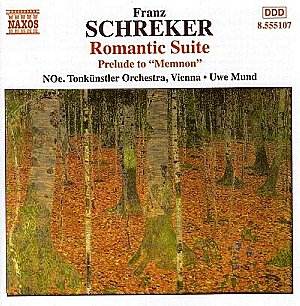

Composer: Franz Schreker

Composer: Franz Schreker

Works: Prelude to ‘Memnon’ (1933), Romantic Suite (1902)

Performers: Tonkünstler Orchestra, Vienna/Uwe Mund

Recording: ORF-Studio, Vienna, March 1988

Label: NAXOS 8.555107

Franz Schreker, once a luminary of the early 20th-century Viennese music scene, has long been relegated to the fringes of the classical canon, often overshadowed by contemporaries like Mahler, Strauss, and Schoenberg. His works, particularly the ‘Romantic Suite’ and the ‘Prelude to Memnon,’ exemplify a lush, impressionistic style that intertwines profound psychological insight with a rich orchestral palette. The recent reissue by Naxos serves as both a reminder of his artistic brilliance and a catalyst for renewed interest in his oeuvre, particularly as Schreker’s music is experiencing a renaissance alongside the broader re-evaluation of neglected composers.

The ‘Prelude to Memnon’ opens with a sonorous horn call that evokes the grandeur of its Egyptian theme, immediately placing the listener in a world of vivid imagery and emotional depth. This piece, initially conceived as a prelude to an opera that never materialized, showcases Schreker’s considerable mastery of orchestral color and melodic contour. The clarinet’s sinuous line, reminiscent of Strauss’s ‘Salome,’ contrasts beautifully with the opulent orchestration, creating an atmosphere of eroticism and mystique. Uwe Mund’s direction allows the Tonkünstler Orchestra to explore the score’s intricate textures, though at times the performance lacks the sumptuousness that this late-Romantic music demands.

In juxtaposition, the ‘Romantic Suite,’ a product of Schreker’s youthful exuberance, displays a confident orchestral handling that mirrors the optimism of the early 1900s. The expansive ‘Idylle’ introduces a thematic richness that is both memorable and evocative, while the subsequent Scherzo bursts with vitality. The third movement, an Intermezzo for strings, emerges as a standout, showcasing Schreker’s ability to create lyrical beauty and intricate interplay among instruments. The final movement, marked ‘Tanz (allegro vivace),’ feels almost symphonic in its scope, culminating the suite with a jubilant flourish. However, while the Tonkünstler Orchestra’s performance is competent, it occasionally falls short of the polished execution that would elevate these works to their fullest potential, particularly in passages that demand a more nuanced and sumptuous sound.

The recording quality, typical of Naxos’s budget line, is adequate but lacks the clarity and depth that would do justice to Schreker’s expansive orchestration. In contrast to the Chandos series featuring the BBC Philharmonic, which captures the opulence of Schreker’s music with greater fidelity and finesse, this Naxos release feels somewhat compromised. Nonetheless, it remains an important document of his work, particularly for those seeking to explore the breadth of early 20th-century music outside the mainstream canon.

The revival of interest in Schreker’s music through recordings like this is essential for understanding the full tapestry of early modernist thought in music. While the performances do not always reach the heights of interpretative brilliance, they offer a valuable glimpse into the lush sound world that Schreker so vividly conjured. This Naxos release, despite its limitations, stands as a worthy introduction to a composer whose music deserves a prominent place in the concert hall and on the recording shelf.