Composer: Sir Thomas Beecham

Composer: Sir Thomas Beecham

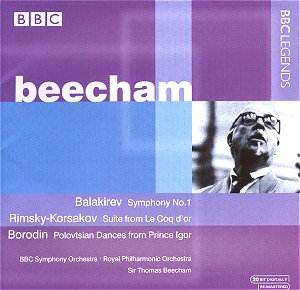

Works: Balakirev: Symphony No. 1 in C major; Rimsky-Korsakov: Le Coq d’Or – Suite; Borodin: Polovtsian Dances

Performers: London Philharmonic Choir; Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Sir Thomas Beecham

Recording: Live recordings from BBC Radio Maida Vale studio (1956) and Royal Festival Hall (1954)

Label: EMI

Sir Thomas Beecham’s affinity for Russian composers is well-documented, and this collection showcases his remarkable interpretive skills alongside the vibrant orchestral textures of Balakirev, Rimsky-Korsakov, and Borodin. The chosen works exemplify the lush, exotic soundscapes characteristic of the Russian nationalist movement, with each piece offering a unique glimpse into the rich tapestry of late Romantic orchestration. Particularly notable is the historical significance of Beecham’s performances, as he was instrumental in introducing many of these works to British audiences, thus widening the scope of the concert repertoire.

The performance of Balakirev’s Symphony No. 1 stands out for its energetic sweep and the intricate interplay of orchestral voices. Beecham’s direction elicits an immediate response from the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, as they navigate the symphony’s complex rhythms with a blend of precision and fervor. The scherzo, in particular, shimmers with an intoxicating vibrancy that captures the essence of the work’s oriental influences. The Andante section, imbued with a languorous charm, paints an evocative picture of a night in the harem, where the strings weave a hypnotic melody that lingers in the air, demonstrating Beecham’s ability to conjure atmosphere through orchestral color and dynamics.

Contrastingly, the suite from Rimsky-Korsakov’s Le Coq d’Or doesn’t quite reach the same heights. While the music is undeniably colorful, the execution feels muted, lacking the robust brilliance that one might expect from this repertoire. The momentum appears somewhat labored, diminishing the suite’s inherent drama. This could be attributed to both the limitations of the mono sound and the recording’s engineering, which, while capturing the immediacy of a live performance, also reveals some unevenness in the orchestral balance. The percussion, for instance, is occasionally overbearing, overshadowing the more delicate string passages.

The disc culminates with Borodin’s Polovtsian Dances, a piece that allows the orchestra to unleash its full vigor, particularly with the inclusion of the London Philharmonic Choir. Here, Beecham’s energetic conducting and the orchestra’s enthusiasm coalesce into a thrilling performance, the choir’s voices soaring above the orchestral foundation with exhilarating clarity. The dance’s infectious rhythms and rich harmonies are executed with abandon, embodying the celebratory spirit of the music.

This recording serves as a valuable artifact of Beecham’s interpretative legacy, capturing not only the exuberance of his performances but also the stylistic nuances of his approach to these Russian masterpieces. While the sound quality may remind contemporary listeners of its vintage origins, the energy and commitment of the musicians shine through, making this a rewarding listen for anyone interested in the evolution of orchestral performance in the mid-20th century. Beecham’s artistry, combined with the spirited playing of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, ultimately affirms this recording as a significant contribution to the classical canon, especially for aficionados of Russian music.