Composer: Richard Strauss

Composer: Richard Strauss

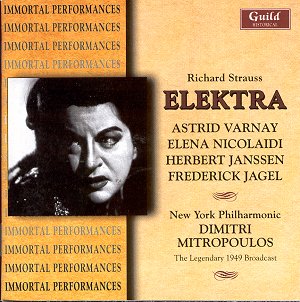

Works: Elektra

Performers: Astrid Varnay (Elektra), Elena Nicolaidi (Klytemnestra), Irene Jessner (Chrysothemis), Herbert Janssen (Orest), Frederick Jagel (Aegisth), Michael Rhodes (Servant), Miriam Stockton, Edith Evans, Elinor Warren, Beverly Dame (slave girls)

Recording: New York Philharmonic, Dmitri Mitropoulos (conductor), Carnegie Hall, New York, 25 December 1949

Label: Guild GHCD 2213/14

Richard Strauss’s Elektra stands as one of the pinnacles of modern opera, a harrowing exploration of vengeance and madness rooted in the mythic landscape of Greek tragedy. Premiered in 1909, the opera’s dense musical texture and psychological complexity demand a level of interpretative artistry that few performers can muster. This recent release featuring Astrid Varnay in the title role is particularly significant, as it represents one of the earliest documented performances of her acclaimed portrayal, conducted by the esteemed Dmitri Mitropoulos.

Varnay’s performance is undeniably the focal point of this recording, and it is a testament to her vocal stamina and technical prowess that she can deliver such an intense portrayal of Elektra’s tortured spirit. From the outset, her opening monologue “Weh, ganz allein” is delivered with a fierce clarity, capturing the character’s isolation and desperation. While Mitropoulos’s enthusiastic pacing occasionally threatens to overshadow the subtleties of the score—particularly in the early ensemble moments—the depth of Varnay’s vocal color provides an anchor amidst the tempest.

Mitropoulos’s interpretation is marked by an impetuous energy that can be both invigorating and disconcerting. The orchestral textures, at times muddled in the chaotic opening motifs, gradually achieve greater clarity as the performance unfolds. His approach to Klytemnestra’s entrance, however, suffers from a lack of gravitas; the urgency with which he propels the music undermines the psychological menace inherent in Strauss’s writing. Elena Nicolaidi’s Klytemnestra, while not particularly sinister in this rendering, manages to navigate the role’s vocal demands with commendable skill, favoring lyrical singing over the more aggressive interpretations often associated with the character.

The performance suffers from some cuts, including the pivotal second scene for Chrysothemis, which diminishes the emotional stakes of the narrative. Irene Jessner’s interpretation of Chrysothemis, while technically proficient, lacks the full-bodied allure that would allow her character to resonate amidst the operatic tumult. The loss of her introspective lament illustrates a missed opportunity to explore the sibling dynamics crucial to the opera’s impact.

Sound quality presents a mixed bag. Although the historical nature of the recording must be considered, the New York Philharmonic’s performance lacks the cohesive fluidity found in studio recordings from the likes of Herbert von Karajan. The orchestral playing, while commendable, occasionally falls short of the dramatic intensity required by Strauss’s score. Moments of disarray, such as the aforementioned opening motif, reveal the orchestra’s struggle with Mitropoulos’s swift tempos.

In juxtaposition with other recordings, particularly those featuring Varnay alongside more reflective conductors, this performance is both compelling and flawed. The emotional peaks, such as Elektra’s frantic search for the axe, are realized with a visceral urgency that leaves a lasting impression. However, one cannot help but feel that a more measured approach could have yielded even greater emotional depth.

This recording of Elektra, despite its technical shortcomings and interpretive inconsistencies, provides invaluable insight into Astrid Varnay’s formidable artistry. The chance to hear her in the role, particularly in such an early performance, is a rare privilege. For those willing to engage with its imperfections, this release offers a glimpse into the raw power of Strauss’s Elektra and the extraordinary vocal talent of one of the 20th century’s great sopranos.