Composer: Ottorino Respighi

Composer: Ottorino Respighi

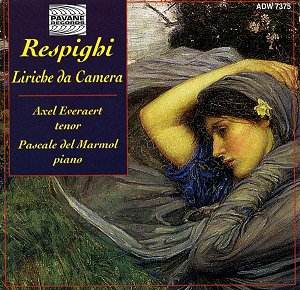

Works: Liriche da Camera – Italian Songs: Deità silvane, I fauni, Musica in horto, Egle, Acqua, Crepusculo, Da cinque canti all’antica: L’udir talvolta nominare, Ballata, Ma come potrei, Bella porta di Rubini, Individual songs: Ultima ebrezza, Pioggia, Lagrime, Tanto bella, Notte, Razzolan, sopra a l’aia le galline, Luce, Soupir, Contrasto, Invito alla danza, Storia breve, Scherzo Notturno

Performers: Axel Everaert (tenor), Pascal del Marmol (piano)

Recording: Recorded at Théâtre La Colonne à Miramas, France, 21-23 April 1997

Label: Pavane ADW 7375

Ottorino Respighi, often overshadowed by his orchestral works like the celebrated “Fountains of Rome,” has cultivated a lesser-known but equally compelling body of vocal music that richly deserves attention. The “Liriche da Camera,” spanning his early years to the 1917 cycle “Deità silvane,” showcases the composer’s lyrical gift and his ability to paint vivid landscapes through song. This collection offers a tantalizing glimpse into Respighi’s formative stylistic influences, particularly his admiration for the melodic lines of Tosti, while also hinting at the more impressionistic colors that would emerge in his later orchestral works.

Axel Everaert’s interpretation presents these songs with a fine balance of sensitivity and lyricism. His silken legato captures the sensuous nature of Respighi’s melodies, particularly in the poignant “Contrasto,” where the words “The moon weeps with slow tears” take on an added depth through Everaert’s nuanced delivery. The tenor’s expressive phrasing invites listeners to immerse themselves in the songs’ emotional landscapes, though at times, his approach feels slightly restrained, lacking the fervor that Leonardo de Lisi brought to the more impassioned works. For instance, Everaert’s rendition of “Ma come potrei” would benefit from a more urgent vocal thrust to evoke the deep yearning embedded in the lyrics.

Pascal del Marmol’s piano accompaniments complement Everaert’s voice beautifully, with a touch that is both delicate and evocative. Particularly notable is the piano writing in “Pioggia,” where the cascading figures effectively evoke the imagery of falling rain, a testament to Respighi’s orchestral sensibilities even in a chamber setting. The interplay between voice and piano is at its most effective in “Razzolan, sopra a l’aia le galline,” where the piano ostinatos reflect the underlying tensions of the narrative. Everaert adeptly navigates the character’s frustration with a vocal line that blossoms and contracts in tandem with the piano’s rhythmic pulse.

Recording quality is commendable, capturing the warmth of both voice and piano in a resonant acoustic space. The clarity of the sound allows for an appreciation of the intricate details in Respighi’s writing, though the absence of the song texts in the booklet is a significant oversight. Given the relatively niche status of Respighi’s vocal works, providing texts would enhance listeners’ understanding of the subtleties and humor interwoven in these songs.

While comparisons with de Lisi’s recording reveal distinct interpretative paths—de Lisi’s robust timbre and more vigorous approach contrasting with Everaert’s lighter touch—each offers valuable insights into Respighi’s art. This collection, while not without its limitations, presents a rewarding listening experience that contributes positively to the growing discography of Respighi’s songs. The intricacies of his vocal writing, paired with the delicate artistry of Everaert and del Marmol, result in a compelling exploration of a composer deserving of greater recognition in the realm of Italian song.