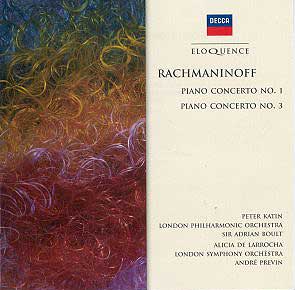

Composer: Sergei Rachmaninov

Composer: Sergei Rachmaninov

Works: Piano Concerto No. 1 (1890), Piano Concerto No. 3 (1909)

Performers: Peter Katin (piano, 1), Alicia de Larrocha (piano, 3), LSO/Previn (3), LPO/Boult (1)

Recording: 1971 (1), 1975 (3), ADD

Label: DECCA

Rachmaninov’s piano concertos, particularly the First and Third, reveal the evolution of a composer whose early struggles gave way to a distinctive voice marked by poignant lyricism and tumultuous emotions. The First Concerto, composed when Rachmaninov was still a student, exhibits a youthful exuberance tempered by the dark shadows of his later works. In contrast, the Third Concerto stands as a monumental testament to his maturity, blending virtuosic demands with profound emotional depth, a reflection of both personal trials and artistic triumphs.

Alicia de Larrocha’s interpretation of the Third Concerto is strikingly poetic, characterized by a leisurely tempo that invites introspection. Her approach is more reminiscent of Schumann’s lyrical qualities than the tempestuous nature typically associated with Rachmaninov. This nuanced interpretation creates a contemplative atmosphere, allowing the themes to evolve organically, much like Medtner’s works, with rich harmonic explorations instead of overt virtuosity. The velvety warmth of the recording enhances this introspective quality, though it may verge on eccentricity as it unfolds in a manner akin to slow-motion photography. The finale, however, pulsates with a vibrant energy, revealing the orchestra’s potent expressiveness under Previn’s direction. The climactic moments are expertly handled, showcasing the ensemble’s pathos and intensity, which ultimately aligns with the ruminative essence of the preceding movements.

On the other hand, Peter Katin’s reading of the First Concerto, while less expansive than de Larrocha’s interpretation, offers a sturdy, mainstream approach that emphasizes clarity and rhythmic precision. Boult’s conducting complements Katin’s style, propelling the performance with a sense of urgency that thrives on the concerto’s dramatic contrasts. The brass section, with its rasping clarity, is particularly noteworthy in the finale, where the tensions build to a thrilling climax. Katin’s interpretation may lack the lyrical depth found in Wild’s or Argerich’s renditions, yet it possesses a directness that can be refreshing, providing a solid entry point into Rachmaninov’s early style.

The engineering quality of these recordings is commendable, capturing the distinct sonorities of both performances while maintaining a balance that allows the piano to soar across the orchestral fabric without overwhelming it. De Larrocha’s recording stands out for its intimate and warm atmosphere, while Katin’s version benefits from a more traditional orchestral sound that emphasizes the concerto’s structural integrity.

Each performance offers a unique lens through which to view these beloved works. De Larrocha’s interpretation is an idiosyncratic journey through Rachmaninov’s Third, inviting listeners to experience the music’s reflective nature, while Katin’s First Concerto delivers a robust, energetic reading that remains steadfast in its adherence to the score’s original intentions. This pairing represents a significant exploration of Rachmaninov’s duality—the lyrical introspection of his mature works versus the fervent energy of his youthful compositions—making it an essential addition for both seasoned aficionados and newcomers to his music.