Composer: Sergei Prokofiev (1878-1953)

Composer: Sergei Prokofiev (1878-1953)

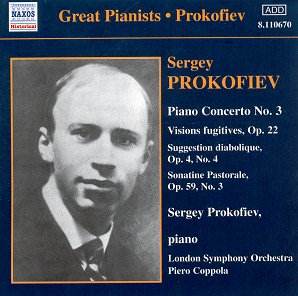

Works: Prokofiev Plays Prokofiev

Performers: Sergey Prokofiev (piano), London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Piero Coppola

Recorded: June 1932 (Piano Concerto No. 3), 1935 (other works)

Label: NAXOS HISTORICAL 8.110670

Duration: 56:18

In the realm of historical recordings, Naxos’s release of Prokofiev Plays Prokofiev serves not merely as a collection of performances but as a vital documentary of the composer’s interpretative vision at the piano. This disc encapsulates the singularity of Prokofiev’s artistry, presenting a rare opportunity to hear the composer himself in a dual role as both creator and interpreter—a phenomenon that remains of profound significance for both musicologists and enthusiasts alike.

The disc opens with the Piano Concerto No. 3, a work emblematic of Prokofiev’s unique voice, blending virtuosic demands with lyrical depth. Recorded in 1932 with the London Symphony Orchestra under Piero Coppola, this performance demands scrutiny not only for its historical context but also for its interpretative choices. Prokofiev’s approach to the piano is characterized by a meticulous clarity of articulation and a nuanced understanding of the orchestral fabric. The recording captures his distinctive blend of forcefulness and finesse; the rapid-fire passages are rendered with a rhythmic precision that invigorates the work’s energetic spirit.

In examining Prokofiev’s performance, one is struck by his subtle use of dynamics. The opening Allegro, with its driving rhythms and intricate interplay between piano and orchestra, showcases Prokofiev’s ability to maintain momentum while ensuring that the piano does not overpower the orchestral palette. This is particularly notable in the second theme, where his lyrical phrasing breathes a sense of warmth that contrasts with the surrounding virtuosity. Such choices mark this recording as a significant alternate interpretation, diverging from the more bombastic tendencies exhibited by later pianists, such as Martha Argerich and Vladimir Ashkenazy, whose renditions often highlight sheer power over textural integration.

The subsequent solo piano works, recorded in 1935, present a somewhat fragmented but nonetheless illuminating portrait of Prokofiev’s pianistic style. Each selection, from the Suggestion diabolique to the Visions fugitives, reveals his rhythmic incisiveness and a penchant for wit, particularly in the Gavotte from the Classical Symphony. Here, Prokofiev’s careful pedaling and articulation yield a performance that captures the playful essence of the piece while maintaining an air of sophistication. His use of rubato is judicious, lending a natural ebb and flow that enhances the melodic line without straying into indulgence.

The engineering quality of these recordings, while reflective of their era, is commendable. The clarity of the piano against the orchestra is notably well-balanced, avoiding the common pitfall of allowing the piano to dominate the orchestral texture. The spontaneity of the orchestra, perhaps less polished than modern counterparts, imbues the performance with an engaging freshness, giving rise to moments of palpable excitement—an interplay that feels both collaborative and competitive, as if both soloist and ensemble are vying for supremacy in a thrilling musical dialogue.

In terms of historical significance, this disc stands out as a testament to Prokofiev’s dual identity as both composer and performer. It encapsulates the transition in his career from the enfant terrible of the St. Petersburg Conservatory to a respected figure in the Western classical canon. The recorded legacy of Prokofiev is limited, with this disc representing the entirety of his commercial recordings as a pianist; it serves as an invaluable resource for understanding his interpretative intentions and performance practice.

When placed alongside notable recordings by other pianists, Prokofiev’s own interpretations offer a different lens through which to view his music. While Argerich’s fiery interpretations and Ashkenazy’s lyrical sensibilities have garnered acclaim, Prokofiev’s performances are infused with an authenticity that is disarmingly direct. His interpretations may lack the visceral excitement of later virtuosos, but they possess a depth that rewards attentive listening—each note is imbued with his distinctive musicality and character.

In conclusion, Prokofiev Plays Prokofiev offers not just a glimpse into the composer’s pianistic prowess but also an essential understanding of his music from the inside out. Naxos’s commitment to preserving and presenting these historical recordings is commendable, and this release stands as an irresistible invitation for listeners to engage with the music of one of the 20th century’s most important composers. For those seeking to understand Prokofiev beyond the notes on the page, this disc is an indispensable resource that resonates with the vitality and innovation of its creator.