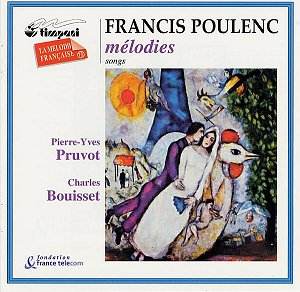

Composer: Francis Poulenc

Composer: Francis Poulenc

Works: Mélodies from Banalités, Chansons Villageoises, Tel Jour Telle Nuit, Chansons Gaillardes, Calligrammes

Performers: Pierre-Yves Pruvot, baritone; Charles Bouisset, piano

Recording: Villa Louvigny, Luxembourg, December 2000

Label: Timpani 1C1061

Francis Poulenc occupies a unique place in the pantheon of 20th-century composers, with his mélodies often viewed as the apotheosis of his musical expression. While he is perhaps more readily recognized for his orchestral and chamber works outside of France, it is through his songs that he reveals his profound connection to poetic language and the human experience. This recording, featuring the baritone Pierre-Yves Pruvot and pianist Charles Bouisset, encompasses a rich tapestry of Poulenc’s output spanning over two decades, showcasing the evolution of his lyrical style from the playful Chansons Gaillardes to the more introspective Calligrammes.

Pruvot’s interpretation of Poulenc’s songs exhibits a forthrightness that is commendable but at times lacks the nuance and emotional depth that the composer so deftly weaves into his music. Unlike the legendary Pierre Bernac—who not only sang Poulenc’s works but was also his interpreter—Pruvot adopts a more direct, almost prosaic approach. This quality can be both refreshing and limiting. In lighter fare such as the Banalités, his solid vocal technique shines; however, the humor can occasionally feel weighty, lacking the devil-may-care spirit that Poulenc’s more whimsical pieces require. In “Les Chemins de l’Amour,” for instance, the lightness of Poulenc’s rhythm begs for a more playful, airy delivery that Pruvot struggles to convey fully.

The more emotionally charged selections, particularly from the cycle Tel Jour Telle Nuit, demand a heightened sensitivity to the text’s complexities. Here, Poulenc’s exploration of themes such as separation and loss calls for a flexibility in phrasing and a delicate coloring of the vocal line that Pruvot’s more straightforward delivery does not fully achieve. In the poignant “La Courte Paille,” for example, the subtle contrasts in dynamics and tempo shifts required to embody the text’s introspection are somewhat muted, leading to a reading that, while sincere, lacks the stirring poignancy found in Bernac’s historic interpretations.

Bouisset’s accompaniment is commendable, providing a supportive yet unobtrusive foundation. His playing is generally well-balanced, allowing Pruvot’s voice to shine through. However, moments such as the Invocation from Chansons Gaillardes reveal a need for greater interaction between voice and piano, where the piano’s expressive potential could more vividly complement the vocal line. The recording itself is clear and well-engineered, capturing the warmth of both voice and instrument without sacrificing detail, although it occasionally feels too polished, lacking the raw emotional resonance one might hope for in a live performance.

Pruvot’s performance is modern in its clarity and technical precision, offering a valuable contrast to the interpretive traditions of earlier generations. While he may not capture the full spectrum of Poulenc’s emotional universe, his interpretation serves as a reminder of the ongoing evolution of vocal performance practice. The disc comprises a thoughtful selection of Poulenc’s mélodies, and while not every moment is revelatory, there are certainly passages of beauty and insight that will resonate with listeners familiar with the repertoire.

This recording stands as a noteworthy contribution to the catalog of Poulenc’s vocal works, providing a fresh perspective that may appeal to both seasoned aficionados and newcomers alike. Yet, it also underscores the challenge of interpreting Poulenc’s intricate emotional landscape, as the balance between technical execution and expressive depth remains a delicate one.