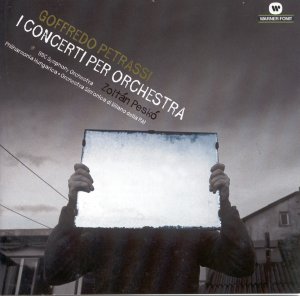

Composer: Goffredo Petrassi

Composer: Goffredo Petrassi

Works: Concerto No. 1 (1934), Concerto No. 2 (1951), Concerto No. 3 (Récréation Concertante, 1953), Concerto No. 4 for string orchestra (1954), Concerto No. 5 (1955), Concerto No. 6 (Invenzione concertata for strings and percussion, 1957), Concerto No. 7 (1964), Concerto No. 8 (1972)

Performers: BBC Symphony Orchestra (1, 2, 7, 8), Philharmonia Hungarica (3, 4), Orchestra Sinfonica di Milano della RAI (5, 6), conducted by Zoltán Peskó

Recording: Rec BBCSO: Maida Vale, London, 8-11 June 1977 and St Pancras Town Hall, 1 June 1978; Hungarica: Marl, Hungary, Dec 1972; RAI: Giuseppe Verdi Hall, Nov/Dec 1979. ADD all stereo

Label: Warner Fonit

Goffredo Petrassi, whose oeuvre often oscillates between neoclassicism and the avant-garde, emerges as a pivotal figure in 20th-century Italian music. The collection of concertos presented here encapsulates a significant evolution in his style, tracing his development from the Stravinskian vigor of the early works to the more complex and sometimes opaque textures of his later compositions. This three-disc set, a revival of earlier Italia LP recordings, offers a comprehensive survey of Petrassi’s concertante output, showcasing his distinctive blend of rhythmic vitality and dodecaphonic experimentation.

The First Concerto is a particularly striking example of Petrassi’s early style, characterized by its robust rhythmic energy and a muscular orchestration that pays homage to Stravinsky. The BBC Symphony Orchestra delivers an exhilarating performance, though moments of imprecision in articulation detract slightly from the overall impact. The second movement, with its echoes of the Venetian polyphonic tradition, is a compelling highlight, though the violin’s melodic line, while spirited, occasionally lacks the warmth necessary to fully engage the listener. The brass, resonating with a fanfare-like exuberance, recalls the climactic release found in Rubbra’s Eleventh Symphony, grounding the piece in a broader orchestral context.

Contrasting sharply with the First Concerto, the Second Concerto embraces a single span, marked by a Bergian lyrical quality. The strings, now more refined, evoke a sense of anxious intimacy, yet they maintain an astringent quality that enhances the work’s ethereal atmosphere. Petrassi’s use of color, informed by Ravel’s orchestral palette, creates a sound world that is both haunting and vivid. This is a significant step forward, aligning him with contemporaries like Benjamin Frankel, who similarly navigated the tensions between lyricism and the complexities of the twelve-tone system.

The Third Concerto further exemplifies Petrassi’s avant-garde tendencies, bursting forth with petulant outbursts reminiscent of Nielsen’s Sixth Symphony. The Philharmonia Hungarica’s performance here is particularly noteworthy; the ensemble’s ability to negotiate the demanding textures speaks to their virtuosic capabilities. This concerto, premiered under Hans Rosbaud, showcases Petrassi’s non-formulaic dodecaphonism, which allows for a more fluid exploration of sonic landscapes. The work’s rhythmic insistence, coupled with its stark contrasts, challenges the listener while inviting them into a world of aggressive dissonance and dynamic interplay.

In stark contrast, the Fourth Concerto, composed for strings alone, emerges as a pinnacle of Petrassi’s artistry. The orchestral writing here is lush and evocative, with the strings achieving an atmospheric transcendence reminiscent of Sibelius’s Fourth Symphony. The recording quality captures the subtle nuances of the ensemble beautifully, allowing the listener to appreciate the creamy, silky tones that permeate the work. This concerto stands as a testament to Petrassi’s ability to evoke profound emotion through the sheer beauty of sound, marking it as a highlight of the collection.

While the Fifth Concerto, commissioned to commemorate the Boston Symphony’s 75th anniversary, delves into a darker emotional landscape, it is buoyed by an ingenious use of thematic material from earlier works. The eerie nostalgia that permeates this piece creates a tapestry of sound that resonates with the listener, though the technical demands placed on the musicians occasionally lead to moments of tension. The Sixth Concerto continues this exploration of narrative through sound, presenting a dialogue between winds and strings that is both elegant and unsettling.

The Seventh and Eighth Concertos, however, reflect a more pronounced shift into the avant-garde, characterized by a chaotic soundscape filled with shrieks and jarring contrasts. These works, while ambitious, may alienate listeners expecting the more lyrical and cohesive structures of the earlier concertos. The performances, while committed, struggle to convey the same level of engagement that is prevalent in the more melodically inclined earlier works.

The recording quality throughout this set is commendably clear, with each ensemble achieving a well-balanced sound that allows the complexities of Petrassi’s orchestration to shine. Zoltán Peskó’s guidance provides a unifying vision across the various performances, bringing a sense of coherence to a diverse and historically significant body of work.

Petrassi’s concertos, particularly the Fourth and Fifth, remain compelling explorations of the 20th-century musical landscape, showcasing a composer whose voice evolved while maintaining a profound connection to the past. Although the later works may challenge the listener with their avant-garde tendencies, the vibrancy of the earlier pieces ensures that this collection is a valuable contribution to the understanding of Petrassi’s legacy.