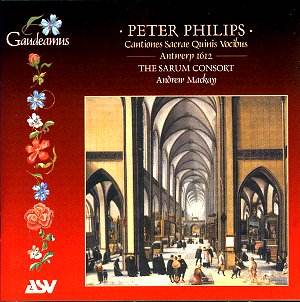

Composer: Peter Philips (1561-1628)

Composer: Peter Philips (1561-1628)

Works: Eighteen Motets from Cantiones Sacrae Quinis Vocibus (1612)

Performers: The Sarum Consort, directed by Andrew Mackay

Recorded at: Milton Abbey, Dorset, August 1999

Label: ASV Gaudeamus GAU 217

Duration: 69:00

Review date: November 2001

Peter Philips, an often-overlooked figure in the rich tapestry of late Renaissance choral music, emerges with renewed vitality in this compelling recording of his Eighteen Motets from the Cantiones Sacrae Quinis Vocibus of 1612. The Sarum Consort, under the adept direction of Andrew Mackay, navigates the intricate polyphonic landscapes of Philips’s motets with a commendable blend of clarity and expressiveness. This recording not only brings Philips’s music to a wider audience but also situates his work within the historical context of his time, reflecting his unique position as a composer in exile.

Philips’s trajectory as a composer is deeply intertwined with his Roman Catholic faith, which necessitated his migration from England to the continent. Born in London and perhaps a choirboy at old St. Paul’s, he left England around 1578, ultimately settling in Antwerp after various sojourns in Italy and Spain. His motets, especially the Cantiones Sacrae, reveal a composer deeply informed by the Italian style, yet firmly rooted in the English choral tradition. As Andrew Mackay notes in the informative booklet, Philips often favored liturgical texts, eschewing the Psalms that were prevalent among his contemporaries. This choice adds a layer of gravitas to his work, allowing for a profound exploration of sacred themes.

The performance choices made by The Sarum Consort are both illuminating and, at times, contentious. The decision to employ a small ensemble for these motets, often characterized by a one-to-a-part approach, yields a distinctly intimate sound. While this may detract from the grandeur associated with larger choral forces—particularly in motets such as “Ascendit Deus,” which typically demands a more forthright approach—the delicate nuances of pieces like “Ave Verum Corpus” benefit from this chamber music aesthetic. Here, the interplay of voices allows for moments of exquisite textural clarity, albeit at the risk of losing some of the works’ intended majesty.

Moreover, the interpretation of the rhythmic aspects, particularly in the Alleluias, reveals a thoughtful deliberation on the part of Mackay and the ensemble. The emphasis on a lilting, madrigalian triple time lends a buoyancy to “Hodie Sanctus Benedictus,” yet one may find the initial entries in “Ascendit Deus” to be slightly underwhelming when contrasted with the more vigorous renditions often favored in cathedral settings. This contrast invites the listener to reconsider the inherent qualities of Philips’s writing, prompting reflections on the environment in which his music was likely performed—smaller chapels rather than grand cathedrals.

Recording quality is commendable, with the acoustics of Milton Abbey contributing to a resonant but controlled sound. The balance between voices and the organ continuo, which often punctuates the harmonies, is well-managed, enhancing the overall listening experience. The engineering captures the clarity of individual voices while maintaining a cohesive ensemble sound, allowing the intricate counterpoint to emerge without becoming muddied.

In the broader scope of choral repertoire, Philips stands as a significant figure, rivaling his contemporaries in both quantity and quality of output. The Cantiones Sacrae reflects a synthesis of English and continental styles, echoing the works of Palestrina while retaining an unmistakable English essence. This recording serves as a vital reminder of Philips’s importance—not just as a composer but as a cultural bridge between two musical worlds.

In conclusion, while The Sarum Consort’s interpretation of Philips’s motets may challenge traditional expectations of choral performance, it offers a fresh and insightful perspective on this remarkable composer. The recording invites listeners to engage with the music on a more intimate level, even as it compels us to reconsider the scale and context of performance. As such, this disc stands as a significant contribution to the ongoing rediscovery of Peter Philips, a composer whose works deserve a far more prominent place in the choral canon.