Composer: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Franz Schubert, Robert Schumann, Frédéric Chopin, Franz Liszt

Composer: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Franz Schubert, Robert Schumann, Frédéric Chopin, Franz Liszt

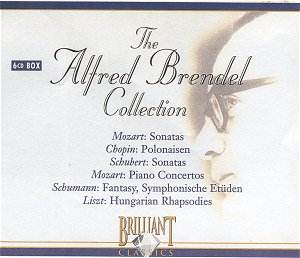

Works: Piano Concerto no. 9 in E flat, K. 271; Piano Concerto no. 14 in E flat, K. 449; Sonata in A minor, K. 310; Fantasy in C minor, K. 396; Rondo in A minor, K. 511; Variations in D on a Minuet by Duport, K. 573; Sonata in C minor, D. 958; Sonata in C, D. 840; Deutschestänze, D. 783; Phantasie in C, op. 17; Symphonic Studies, op. 13; Polonaise in A flat, op. 53; Polonaise in C minor, op. 40/2; Polonaise in F sharp minor, op. 44; Polonaise-Fantaisie in A flat, op. 61; Andante spianato et Grande Polonaise brillante in E flat, op. 22; Hungarian Rhapsodies nos. 2, 3, 8, 13, 15, 17; Csárdás obstiné

Performers: Alfred Brendel (piano), I Solisti di Zagreb; Antonio Janigro (conductor)

Recording: Recorded Vienna, 1966-1968

Label: Brilliant Classics

The Alfred Brendel Collection, spanning six CDs, presents a remarkable journey through the classical piano repertoire, showcasing the artistry of one of the 20th century’s most revered pianists. Brendel’s interpretations of works by iconic composers—Mozart, Schubert, Schumann, Chopin, and Liszt—reveal not only his technical prowess but also a deep intellectual engagement with the music. This collection, recorded between 1966 and 1968, encapsulates Brendel’s early maturity, a period that would lay the groundwork for his illustrious career.

In the first volume, Brendel’s interpretations of Mozart’s Piano Concertos nos. 9 and 14 stand out for their unforced brilliance and buoyancy. The partnership with I Solisti di Zagreb under Antonio Janigro brings a compelling warmth and vitality to the orchestral textures. Brendel’s playful exuberance in the outer movements of K. 271 and K. 449 contrasts elegantly with the introspective depth he achieves in the slow movements. While Marriner’s later recording of K. 449 presents a more polished interpretation, Brendel’s naturalness and joy resonate more authentically, particularly in the ebullient exchanges between piano and orchestra.

Volume two shifts focus to Mozart’s solo piano works, with the A minor Sonata as a hallmark of Brendel’s interpretative clarity. His adherence to the “Allegro maestoso” marking is notable, imbuing the opening theme with a dignified grandeur that elevates the music beyond its technical demands. Brendel’s slow, lyrical approach to the subsequent movements allows for emotional depth, particularly in the Rondo, where the expansive tempo reveals hidden textures often overlooked by more hurried interpretations. His ability to breathe life into the Variations on a Minuet by Duport underscores his affinity for Mozart’s delicate craftsmanship.

Brendel’s engagement with Schubert’s Sonatas in volume three reveals a more complex relationship. The C minor Sonata’s first movement is executed with a fierce intensity that, while dazzling, sometimes sacrifices the fluid ease characteristic of Schubert’s music. The tension between brilliance and lyrical flow becomes apparent, particularly in the slow movement, where a more fluid tempo could enhance its emotional resonance. The C major Sonata, in contrast, benefits from a more flowing interpretation, showcasing Brendel’s ability to navigate the nuances of Schubert’s melodic language with sensitivity.

Schumann’s Phantasie in C, op. 17, featured in volume four, serves as a litmus test for Brendel’s interpretative style. His approach is undeniably thoughtful, but at times he risks veering into the overly cerebral, particularly in the first movement. The finale, however, illustrates Brendel’s poetic touch, transforming the emotional landscape into a tapestry of sound that is both compelling and deeply felt. The Symphonic Studies demonstrate his dexterity and adherence to Schumann’s markings, showcasing a performance that is both technically assured and expressively potent.

In volume five, Brendel’s foray into Chopin is intriguing, albeit somewhat detached compared to the more passionate interpretations of specialists. His interpretations, particularly of the Polonaise-Fantaisie and Andante spianato, exhibit a grand energy and structural integrity that challenge conventional renditions. Nevertheless, the absence of a more innate national fervor leaves the performances feeling slightly academic. The energy is palpable, yet one longs for the sheer exuberance that typifies the best Chopin interpretations.

The collection concludes with Brendel’s vibrant readings of Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies, where his affinity for the composer’s lyrical and virtuosic demands shines through. Brendel’s refusal to sanitize the emotional and gypsy elements of the music reveals an underlying sincerity, presenting Liszt not merely as the flamboyant showman but as a composer of profound depth. The engineering of the recordings allows the listener to appreciate the subtleties of Brendel’s touch, with the sound quality retaining its clarity despite the passage of time.

This collection is a significant testament to Brendel’s artistry during a pivotal stage of his career. It offers listeners a rich tapestry of interpretations that, while occasionally controversial, are always deeply considered. Brendel’s performances are not merely technical displays; they are thoughtful explorations that invite us to reconsider the familiar works of the classical canon. Therefore, for both seasoned aficionados and newcomers alike, the Alfred Brendel Collection is an essential addition to any classical music library, illuminating the transformative power of interpretation through the lens of one of the great pianists of our time.