Composer: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791), Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714-1787), Josef Myslivecek (1737-1781)

Composer: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791), Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714-1787), Josef Myslivecek (1737-1781)

Works: La clemenza di Tito: Parto, ma tu, ben mio; Paride ed Elena: Le belle immagini d’un dolce amore; Abramo ed Isacco: Chi per pietà mi dice – Deh, parlate, che forse tacendo; Le nozze di Figaro: Voi che sapete; Antigona: Sarò qual è il torrente; Idomeneo: Ah qual gelido orror – Il padre adorato; Paride ed Elena: O del mio dolce ardor; Lucio Silla: Dunque sperar poss’io – il tenero momento; La finta giardiniera: Va’ pure ad altri in braccio; L’Olimpiade: Dunque Licida ingrato – Più non si trovano; La clemenza di Tito: Se mai senti spirarti sul volto; L’Olimpiade: Che non mi disse dì!; La clemenza di Tito: Deh, per questo istante solo

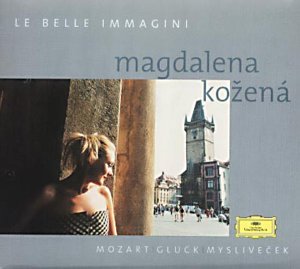

Performers: Magdalena Kozena (mezzo-soprano), Prague Philharmonia/Michel Swierczewski

Recording: Dvorak Hall, Prague, September 2001

Label: Deutsche Grammophon 471 334-2 [68:18]

The works gathered in “Le Belle Immagini” present a fascinating juxtaposition of three composers who shaped the operatic landscape of the 18th century. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s operas, brimming with melodic inventiveness and dramatic depth, sit alongside Christoph Willibald Gluck’s reformist ethos and Josef Myslivecek’s lyrical gifts. The selection, curated by mezzo-soprano Magdalena Kozena, offers a glimpse into the rich tapestry of operatic expression during a transitional period when the emotional weight of the music began to eclipse the rigid formalism of earlier styles.

Kozena’s voice, characterized by its lightness and agility, serves as an apt vehicle for this repertoire. The recording opens with a poignant interpretation of “Parto, ma tu, ben mio” from La clemenza di Tito, where Kozena’s nuanced phrasing brings out the character’s emotional turmoil. The lyricism inherent in this aria is complemented by the Prague Philharmonia’s sensitive accompaniment under Michel Swierczewski’s direction, which maintains a balance between orchestral color and vocal clarity. There is a palpable sense of urgency in her delivery, particularly in the crescendos that culminate in a hauntingly soft conclusion, showcasing her command over dynamic range.

Throughout the album, Kozena navigates the technical demands of the repertoire with impressive artistry. In Myslivecek’s “Voi che sapete,” the coloratura passages are executed with precision, though one might argue that her interpretation lacks the dramatic intensity found in Cecilia Bartoli’s renowned performances. Kozena opts for a more straightforward interpretation, which, while lacking Bartoli’s flamboyance, allows for the beauty of the melody to shine through without distraction. The artistry in her rendition lies in the subtlety of her interpretation rather than in overt bravura.

Recording quality plays a pivotal role in the overall experience. The sound engineering captures the warmth of Kozena’s voice and the rich timbres of the orchestra, allowing for a clear delineation of instrumental lines. The acoustic of Dvorak Hall enhances the depth of sound, creating an enveloping listening environment. However, at times, the balance between voice and orchestra could be more finely tuned, as certain orchestral passages occasionally overshadow Kozena’s more delicate phrases.

Comparisons with other recordings of similar repertoire reveal the strengths and weaknesses of Kozena’s approach. While Bartoli’s interpretations are often celebrated for their emotional fervor and technical brilliance, Kozena’s focus on lyricism and refinement offers a fresh perspective that should not be overlooked. In Gluck’s “Se mai senti spirarti sul volto,” for instance, Kozena’s interpretation is marked by a gentle touch that evokes the tender longing of the text, contrasting sharply with Bartoli’s more dramatic take. This serves to highlight the diversity within the mezzo-soprano repertoire and the interpretative choices available to artists.

Kozena’s exploration of the lesser-known Myslivecek alongside the more familiar Mozart and Gluck is commendable, as it invites listeners to reconsider the contributions of this often-overlooked composer. The aria “Dunque Licida ingrato” exemplifies Myslivecek’s melodic ingenuity, with its bittersweet undertones perfectly rendered by Kozena’s expressive phrasing. The orchestration supports her voice admirably, providing a rich backdrop that enhances the emotional narrative without detracting from the vocal line.

This recording, while it may not redefine the boundaries of the mezzo-soprano repertoire, stands as a testament to Kozena’s artistry and her ability to illuminate both well-known and obscure works. The collection serves as an eloquent reminder of the interplay between voice and orchestral texture in the operatic tradition, while also offering a platform for discerning listeners to engage with a rich historical context. The album is a worthy addition to any collection, particularly for those who appreciate the subtleties of operatic interpretation.