Composer: Olivier Messiaen

Composer: Olivier Messiaen

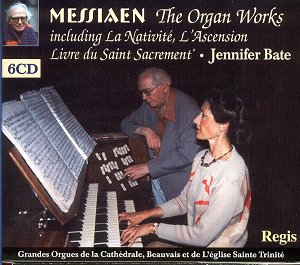

Works: Complete Organ Works

Performers: Olivier Latry, Jennifer Bate

Recording: Recorded in the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris, July 2000 (Latry); Recorded in Beauvais Cathedral 1980-82 and Eglise du Saint-Trinité, Paris, May 1987 (Bate)

Label: Deutsche Grammophon, Regis

Olivier Messiaen stands as a towering figure in 20th-century music, renowned for his innovative harmonic language and deep spiritual expression. His organ works, a crucial component of his oeuvre, reflect both his Catholic faith and his fascination with nature, particularly through the incorporation of birdsong and exotic rhythms. The recent releases of the complete organ works by Olivier Latry and Jennifer Bate afford a comprehensive survey of Messiaen’s evolving style from the early mysticism of “Le Banquet Céleste” (1932) to the intricate complexity of “Livre du Saint Sacrement” (1984). These recordings not only document the breadth of Messiaen’s compositional techniques but also offer insights into the interpretative choices made by these distinguished organists.

Latry’s recording, captured in the resplendent acoustic of Notre-Dame, benefits from a sonic depth that enhances the grandeur of Messiaen’s music. The engineering feat of employing twelve microphones allows for a kaleidoscopic range of colors, offering clarity in the dense textures typical of “Les yeux dans les roues” from “Livre d’Orgue.” The precision of the recording reveals the rhythmic intricacies that can often be overwhelmed by the sheer volume of sound. Latry’s interpretations are marked by an urgency that pulls the listener into Messiaen’s world; his lively tempos and keen sense of pulse in the “La Nativité du Seigneur” cycle juxtapose the serene moments with a vibrant energy that underscores the duality present in Messiaen’s music.

Conversely, Bate’s interpretations, recorded in the more resonant acoustics of Beauvais, exude a contemplative quality. Her slower tempos in works such as “Les Corps Glorieux” permit a spaciousness that allows for meditation on the music’s theological underpinnings. While her readings are meticulous and nuanced, at times they risk sacrificing the rhythmic vitality that characterizes Messiaen’s work. The comparison is particularly striking in “La Verbe,” where Bate’s more expansive phrasing contrasts with Latry’s incisive articulation. This divergence in interpretation highlights the varied approaches to the same score, showcasing how tempo and registration choices can drastically alter the listener’s experience.

A notable aspect of both recordings is their treatment of Messiaen’s complex rhythmic language. Latry’s interpretation of “Soixante-Quatre Durées” exemplifies his meticulous attention to rhythm, capturing the essence of Messiaen’s serial techniques with a blend of clarity and exuberance. In contrast, Bate’s approach to the same piece tends to blur some of these intricate details, resulting in a less defined rhythmic structure. This divergence emphasizes the importance of the performer’s vision in conveying Messiaen’s multifaceted style. While both organists demonstrate exceptional technical prowess, it is Latry’s ability to maintain a firm grasp of the rhythmic pulse that ultimately resonates more profoundly in this instance.

The historical context of these works cannot be overlooked. Messiaen composed “Livre du Saint Sacrement” during a period of great personal and artistic significance, grappling with his faith and the legacy of his earlier compositions. Bate’s interpretation of “Livre du Saint Sacrement,” which she premiered, embodies a deep connection to the work, yet Latry’s more straightforward interpretation captures the essence of the music’s narrative thread—his reading feels less encumbered by the weight of history, allowing the work’s inherent joy and complexity to emerge more vividly.

The sonic qualities of each recording further enhance the distinctions between the two interpretations. Latry’s vibrant sound palette, enhanced by the acoustic of Notre-Dame, allows the various timbres of the organ to emerge with remarkable clarity, particularly in the loud, climactic passages of “Dieu parmi nous.” Conversely, Bate’s recordings, while rich and resonant, can at times obscure the rapid, intricate passages, such as those in “Les yeux dans les roues,” where the dense texture challenges the listener’s ability to discern individual lines.

Latry’s inclusion of previously unpublished works such as “Monodie” from 1963 enriches his already compelling set, providing listeners with a glimpse into the composer’s lesser-known compositions. This commitment to presenting the entirety of Messiaen’s organ oeuvre positions Latry’s recording as essential for both enthusiasts and newcomers alike. Bate’s collection, while lacking in some of this novelty, remains an invaluable resource for its historical importance and emotional insight.

Latry’s interpretation stands out for its dramatic instincts and vivid recording quality, setting a benchmark in the realm of Messiaen’s organ music. His dynamic approach, combined with the exceptional engineering of the Deutsche Grammophon release, captures the vibrancy and complexity of Messiaen’s language. Bate’s interpretations, defined by their introspective nature and historical significance, also deserve recognition for their contribution to understanding this pivotal repertoire. The choice between these two outstanding recordings ultimately reflects the listener’s preference for either a vibrant, urgent approach or an introspective, meditative exploration of Messiaen’s profound musical universe.