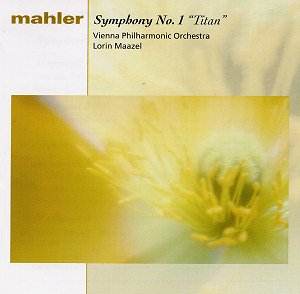

Composer: Gustav Mahler

Composer: Gustav Mahler

Works: Symphony No. 1 in D major

Performers: Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, Lorin Maazel (conductor)

Recording: Recorded in the Musikverein, Vienna in 1986

Label: Sony Essential Classics SBK89783

Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 1, often dubbed “Titan,” represents a seminal point in the evolution of the symphonic form, bridging the late Romantic era and the burgeoning modernism of the early 20th century. Premiered in 1889, this work encapsulates Mahler’s distinctive voice, characterized by a unique fusion of folk elements, grand orchestral textures, and profound emotional depth. The symphony’s trajectory mirrors Mahler’s own artistic journey, oscillating between the bucolic and the existential. Lorin Maazel’s recording with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra stands as part of a comprehensive Mahler cycle from the 1980s—a period noted for its rich interpretative possibilities. However, this particular interpretation reveals significant shortcomings in conveying the youthful exuberance and complexity inherent in Mahler’s score.

The orchestral playing is, without question, of the highest caliber. The Vienna Philharmonic’s sound is lush and sonorous, perfectly capturing the spacious acoustic of the Musikverein. The opening movement’s atmospheric introduction, with its distant echoes of nature, is well-executed, yet once the “Wayfarer” theme emerges, the interpretation falters under Maazel’s heavy-handed approach. The lyrical and romantic elements, while beautifully rendered, overshadow the youthful vitality that pulses through the music. Maazel’s tendency to linger too long on phrases—despite average clock timings—creates an impression of dragging rather than soaring. The climactic recapitulation, intended to be a cathartic release, becomes a bloated moment that lacks the necessary urgency, leading to an incongruous coda that rushes forward in a manner that feels disjointed.

The second movement, marked “Ländler,” suffers similarly. A dance of rustic charm should burst forth with spirited energy, yet here, the rhythmic snap is muted. Instead of allowing the ländler’s inherent buoyancy to shine, Maazel’s interpretation leans toward a ponderous heaviness that stifles the music’s playful character. The third movement, often lauded for its sharp contrasts and visceral intensity, is rendered too polished and sophisticated, stripping away the raw edges that Mahler intended. This transformation into something more “respectable” not only dulls the music’s inherent impudence but also misrepresents the spirit of the time in which it was composed.

While the final movement boasts grandeur and is performed with technical precision, it ultimately does not redeem the performance. The overarching agenda appears to prioritize beauty and a warm glow over the multifaceted emotional landscape Mahler was exploring. The contrasts of desperation and triumph, which pulse through the music, are softened to the detriment of the overall impact. Comparatively, recordings by conductors such as Rafael Kubelik, Bruno Walter, and Bernard Haitink offer a more robust grasp of Mahler’s intent. These interpretations not only respect the composer’s intricate textures but also evoke the spirited defiance and emotional volatility that characterize his early symphonic works.

Maazel’s recording, while undeniably superb in terms of orchestral execution and sound quality, ultimately fails to engage with the heart of Mahler’s Symphony No. 1. The interpretative choices made create a performance that feels more enamored with surface beauty than with the substantive emotional journey that Mahler offers. As such, this recording finds itself overshadowed by those that more effectively capture the spirit, complexity, and youthful exuberance of Mahler’s symphonic vision.