Composer: Lily Pons

Composer: Lily Pons

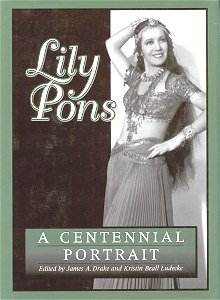

Works: A Centennial Portrait, edited by James A. Drake and Kristin Beall Ludecke

Performers: Various contributors

Recording: N/A

Label: Amadeus Press

The centennial celebration of Lily Pons, an iconic figure in 20th-century opera, provides a rich opportunity to examine her legacy through the lens of the edited collection “Lily Pons: A Centennial Portrait.” While Pons is often remembered for her glamorous persona and vibrant stage presence, the essays and reflections within this volume reveal the complexities of her artistry and the challenges of her career. The book offers varied perspectives but ultimately presents a disjointed narrative that lacks the chronological coherence that would have better served her multifaceted story.

The collection encompasses a variety of essays and comments from contributors, yet it suffers from a lack of unifying structure, akin to rearranging the chapters of a Dickens novel. This absence of chronological order makes it challenging for the reader to grasp the trajectory of Pons’ career—from her early beginnings in France to her notable successes in Italian opera and her ventures into film. Her repertoire, while undeniably popular, was somewhat limited; she thrived in the works of Donizetti and Verdi but seldom ventured into the more demanding realms of Wagner, which raises questions about the breadth of her vocal abilities. The book hints at her desire for multifaceted success—straddling the line between serious artist and glamorous entertainer—but it does so without adequately exploring the implications of this duality.

Critically, Pons’ voice, which was celebrated for its bright timbre and agility, also had its limitations. Notably, her interpretations of significant coloratura roles, such as the Mad Scene in Donizetti’s “Lucia di Lammermoor,” reveal both her technical prowess and her occasional shortcomings. The editorial choices in the anthology do not sufficiently address these nuances, leaving the reader to navigate Pons’ recorded legacy alone. Her recordings, while often charming, contain instances of pitch inaccuracies and missed notes, particularly in demanding passages that challenge even the most skilled singers. A comparative listening of her rendition of “Il dolce suono” against that of contemporaries elucidates these discrepancies, showcasing a contrast in interpretative depth and technical precision.

The sound quality of the recordings associated with Pons remains a point of contention. While her early 78s possess a certain historical charm, they often suffer from the limitations of their time, with surface noise and dynamic range hindering full appreciation of her vocal artistry. In contrast, some remastered versions attempt to elevate her sound but can fall short of capturing the immediacy and nuance of live performance. The anthology would have benefitted from a more rigorous exploration of these recordings, perhaps supported by analyses from sound engineers or historians who understand the intricacies of audio fidelity.

The collection’s attempts to paint a portrait of Lily Pons ultimately reveal more about the challenges of presenting a coherent narrative than they do about the singer herself. While her star shone brightly during her lifetime, the disjointed nature of the essays and the lack of critical depth may leave readers longing for a more structured and thorough investigation of her life and artistic contributions. Pons remains a fascinating figure, embodying the complexities of a performer caught between the demands of high art and popular appeal, but this anthology does not fully realize her potential as a subject worthy of exploration. The task of illuminating her legacy continues, and one hopes for a future work that will do justice to the depth and breadth of her career.