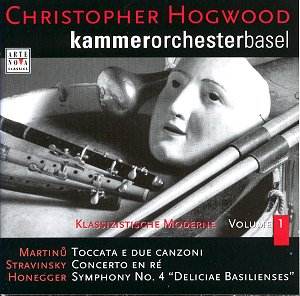

Composer: Arthur Honegger

Composer: Arthur Honegger

Works: Symphony No. 4 “Deliciae Basilienses” (1946), Martinu’s Toccata e Due Canzoni (1946), Stravinsky’s Concerto in Ré (1946)

Performers: Kammerorchester Basel, Christopher Hogwood (conductor)

Recording: Rec Radio Studio Zurich, Switzerland, 8-9 March 2001

Label: Arte Nova 74321-86236-2

Arthur Honegger, a prominent figure of the early 20th-century French music scene, is often overshadowed by his more illustrious contemporaries. His Fourth Symphony, subtitled “Deliciae Basilienses,” composed in 1946, emerges as a product of its time—reflecting a post-war sensibility that sought to reconcile the joys of life amidst the ruins of conflict. This work exemplifies Honegger’s characteristic blend of lyricism and rhythmic vitality, yet it also reveals a certain ambivalence that may frustrate listeners seeking the emotional depth found in his earlier symphonic endeavors.

The performances on this recording, under the baton of Christopher Hogwood, bring together Honegger’s symphony alongside Martinu’s lively Toccata e Due Canzoni and Stravinsky’s Concerto in Ré. While Hogwood is renowned for his work with period instruments, the sound achieved in this recording feels somewhat anemic, particularly for a piece that yearns for robust orchestral color. The Kammerorchester Basel, while competent, appears to struggle with the architectural demands of Honegger’s work. The orchestra’s thin texture detracts from the symphonic narrative, leaving moments that should resonate with intensity feeling rather pallid.

Hogwood’s interpretation of Martinu’s Toccata is, by contrast, full of infectious energy. The piano part, performed with gusto by Florian Hölscher, shines in the ensemble’s buoyant approach, capturing the exuberance inherent in Martinu’s American period. The brisk tempos and clear articulation allow the music’s playful character to emerge, making this performance a highlight of the disc. The Stravinsky piece, while less frequently performed than his more celebrated works, reveals a complexity that Hogwood navigates with skill. The angular lines and rhythmic drive are well articulated, yet a more opulent string sound would enhance the work’s emotional undercurrents.

Returning to Honegger’s Fourth Symphony, the slow movement falters due to the lack of expressive depth in the woodwinds, which struggle to inject color into lines that can come across as banal. The symphony’s structure, which oscillates between moments of lightness and more somber reflections, could greatly benefit from an interpretation that embraces greater dynamic contrasts. The result is a performance that, while technically proficient, feels ultimately unfulfilled.

This disc, while offering notable moments, particularly in Martinu’s Toccata, ultimately serves as a reminder of the challenges inherent in Honegger’s symphonic output and the interpretative choices that frame it. The recording’s engineering captures the orchestra with clarity, yet it lacks the vibrancy necessary to elevate these works to the level of the most memorable performances. As the first volume in a series exploring the legacy of Paul Sacher and the works he championed, it suggests a promising future, though this particular iteration may leave listeners wanting more in terms of interpretative depth and orchestral richness. The exploration of Honegger’s symphonic voice continues to be a worthy endeavor, albeit one that requires a more compelling artistic approach to fully resonate.