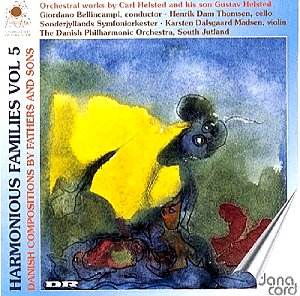

Composer: HELSTED

Composer: HELSTED

Label: DANACORD DACOCD 537

Performers: Karsten Dalsgaard Madsen – Violin, Henrik Dam Thomsen – Cello, Giordano Bellincampi, conductor, The Danish Philharmonic Orchestra, South Jutland

Recorded: Musikhuset, Sonderborg, August 2000

Duration: [68.02]

In the fifth installment of Danacord’s series celebrating familial legacies in Danish music, we encounter the works of Carl and Gustav Helsted, two composers whose lives and careers were steeped in the shadow of their contemporaries. This recording presents Carl Helsted’s Symphony No. 1 in D (c. 1841/42) and Overture in D (1841), alongside Gustav Helsted’s Romance for Violin and Orchestra (1888) and Concerto for Cello and Orchestra in C, Op. 35 (1919). While the disc is noteworthy for its commitment to unearthing lesser-known repertoire, it ultimately raises questions about the enduring legacy of the Helsted name in the pantheon of classical music.

The Symphony No. 1, described in the accompanying notes as “conventional,” presents a polished façade yet lacks the spark of innovation that might elevate it beyond its historical context. One finds in its four movements an adherence to classical forms, replete with lyrical themes, but the thematic material often feels derivative, echoing the influences of Gade rather than establishing its own voice. The opening Allegro con brio, for example, while deftly orchestrated, unfolds like a series of pleasant yet forgettable musical phrases. The string writing is competent, yet it lacks the emotional depth that one might find in the symphonic works of contemporaries like Mendelssohn. The second movement, an Adagio, offers moments of introspection, but again, one is left yearning for a more profound exploration of its potential.

The Overture in D fares slightly better, showcasing a vigorous energy and a clear understanding of orchestral color. Helsted’s orchestration is bright, particularly in the woodwinds, which evoke a buoyant spirit that is somewhat reminiscent of Gade’s own overtures. However, the thematic material remains fairly straightforward, lacking the twists and development that would render it memorable. The performance under Giordano Bellincampi is commendable—his baton effectively managing the orchestra through the passages, ensuring clarity and precision in the ensemble.

Turning to Gustav Helsted, the Romance for Violin and Orchestra represents a charming foray into the lyricism that characterizes the late Romantic idiom. Violinist Karsten Dalsgaard Madsen approaches the work with a sensitivity that brings out its melancholic nuances. The piece unfolds with a lyrical ease, and the interplay between soloist and orchestra is particularly well-realized, with Madsen’s phrasing infused with a heartfelt expressiveness that brings the work to life. The Romance, while not groundbreaking, is a delightful addition that deserves the occasional performance.

In stark contrast, Gustav’s Concerto for Cello and Orchestra is a more ambitious endeavor, albeit one that does not fully coalesce into a cohesive statement. The work’s brevity—clocking in at just over 22 minutes—does not preclude a sense of fragmentation that emerges in its erratic modulations. Cellist Henrik Dam Thomsen performs with assurance, navigating the work’s technical challenges with aplomb. Yet, the concerto’s lack of formal unity leaves one pondering its impact. For instance, the central Scherzo, while lively, feels disjointed from the lyrical opening, leading to a conclusion that fails to resonate as strongly as one might hope.

One cannot overlook the historical significance of these works, particularly in the context of Danish music, which often grapples with the overshadowing presence of Gade and later, Nielsen. Both Carl and Gustav Helsted occupy niches that, while not revolutionary, reflect a period of transition within the Danish soundscape. Their music speaks to a tradition that values craftsmanship, yet it simultaneously reveals a reticence to fully embrace the innovations that were emerging elsewhere in Europe.

The recording quality is commendable, capturing the orchestra’s texture with clarity and warmth. The balance between the soloists and the ensemble is handled with care, allowing for the intricate dialogues within the pieces to emerge without sacrificing the orchestral fabric.

In conclusion, while this volume of Danacord’s exploration into Danish familial music may not ascend to the heights of its predecessors, it offers an informative glimpse into the works of the Helsted family. The performances are executed with sincerity and skill, rendering even the more conventional works worthy of attentive listening. The disc serves as a reminder that not every piece of music needs to resonate through the ages; sometimes, the beauty lies in the craftsmanship itself, even if it does not leave an indelible mark on the listener’s memory. Thus, the Helsteds, while perhaps not destined for the concert hall’s permanent fixtures, deserve recognition for their contributions to the rich tapestry of Danish music.