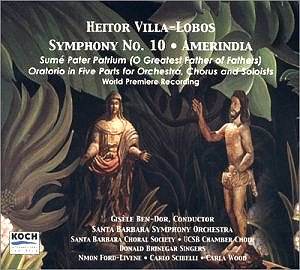

Composer: Heitor Villa-Lobos

Composer: Heitor Villa-Lobos

Works: Symphony No. 10: “Amerindia”

Performers: Carla Wood (mezzo-soprano), Carlo Scibelli (tenor), Nmon Ford-Livene (bass-baritone), Santa Barbara Choral Society, USCB Chamber Choir, Donald Brinegar Singers, Santa Barbara Symphony Orchestra / Gisèle Ben-Dor

Recording: KOCH INTERNATIONAL CLASSICS 3-7488-2 [c.52.00]

Label: KOCH INTERNATIONAL CLASSICS

Heitor Villa-Lobos remains a towering figure in the landscape of 20th-century classical music, celebrated for his ability to weave Brazilian folk elements into a modernist framework. His Tenth Symphony, subtitled “Amerindia,” premiered in Paris in 1957 as a tribute to the 400th anniversary of São Paulo. This monumental work, characterized by its choral and orchestral texture, presents a fascinating, if flawed, exploration of historical themes through a lens that feels as much like an oratorio as a symphony. The recent release from Koch International Classics brings this ambitious score to life, offering both a historical context and a fresh perspective on its intricate musical fabric.

The performance, under the baton of Gisèle Ben-Dor, commands attention for its vibrant energy and commitment to the often sprawling musical narrative. The Santa Barbara Symphony Orchestra delivers a robust account, showcasing the lush orchestrations typical of Villa-Lobos, yet at times the textures risk overwhelming the choral elements, particularly in the climactic fourth movement, “De Beata Virgine Dei Mater Maria.” The movement’s lengthy duration—nearly a quarter of the entire symphony—functions as a suite, yet the dramatic tension that should accompany such a structural choice feels diluted amidst the rich orchestration. The choral writing, while earnest, lacks the refinement found in Villa-Lobos’s more polished choral works, such as those on Hyperion’s acclaimed recordings of his sacred music.

Ben-Dor’s interpretation navigates the work’s inherent dichotomies, from the pastoral “War Cry,” which evokes a wistful lament rather than a rallying cry, to the exuberant scherzo, “Iurupichuna,” that plays with the notion of a Brazilian folk spirit. The blend of voices and orchestra is generally effective, yet the soloists—Carla Wood, Carlo Scibelli, and Nmon Ford-Livene—often deliver with more vigor than nuance. This aligns well with the overall aesthetic of the piece, but the lack of subtlety in the vocal lines can occasionally detract from the narrative’s emotional depth. The engineering quality of the recording captures the orchestra’s fullness, albeit occasionally at the expense of the soloists’ clarity.

Villa-Lobos’s choral writing in “Amerindia” is particularly noteworthy for its reliance on textural color rather than intricate counterpoint. The closing movement, “Glory in Heavens and Peace on Earth,” encapsulates this approach, offering a rousing affirmation that, while thematically hollow to some listeners, serves as a fitting conclusion to this sprawling work. The balance between the choral forces and the orchestra is a point of contention; while the orchestral sound is grand and enveloping, it sometimes overshadows the nuances of the vocal lines.

The Koch recording, while not poised to dethrone the more refined interpretations of Villa-Lobos’s choral repertoire, stands as a commendable addition for those interested in the broader spectrum of his symphonic output. The performance reflects a deep engagement with the score’s cultural and historical significance, and while it may not achieve the heights of the composer’s most celebrated works, it remains an essential exploration of Villa-Lobos’s complex musical identity. For enthusiasts of this composer, “Amerindia” offers a rich tapestry of sound and thought, deserving of exploration alongside more familiar masterpieces like the “Bachianas Brasileiras.”