Composer: George Frideric Handel (1685-1759)

Composer: George Frideric Handel (1685-1759)

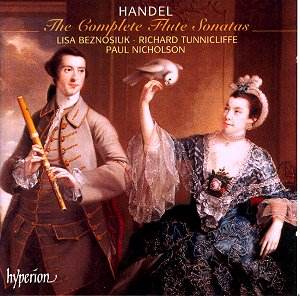

Works: The Complete Flute Sonatas (Sonata in G major HWV363b, Sonata in E minor HWV379, Sonata in B minor HWV367b, Sonata in E minor HWV359b, Sonata in A minor HWV374, Sonata in E minor HWV375, Sonata in B minor HWV376, Sonata in D major HWV378)

Performers: Lisa Beznosiuk (flute), Richard Tunnicliffe (cello), Paul Nicholson (harpsichord)

Recording: Hyperion CDA67278

Release Date: June 1994 and January 2001

Length: 72.30

In the realm of baroque chamber music, Handel’s flute sonatas hold a somewhat ambiguous place. The recent recording of Handel’s complete flute sonatas by Hyperion, featuring the eloquent flutist Lisa Beznosiuk alongside the accomplished continuo duo of Richard Tunnicliffe and Paul Nicholson, invites both appreciation and contemplation of this repertoire’s nuanced complexities.

Handel’s so-called “Opus 1” comprises a collection of sonatas, some of which are indeed attributed to him, while others are of uncertain provenance, likely assembled by publishers eager to capitalize on his renown. The eight sonatas presented here—seven of which are part of the original opus—are a testament to Handel’s ingenuity, yet they often reveal a curious imbalance in their musical weight.

The opening Sonata in G major HWV 363b (Op 1 No 5) begins with an Allegro that is vibrant and engaging, allowing Beznosiuk’s flute to dance atop the lively continuo. Her articulation in the fast passages is commendable, characterized by crisp staccatos and fluid legato that deftly navigate the florid passages. This contrasts sharply with the more subdued Andante, which, while beautifully played, exposes a greater tendency toward monotony in the slower movements throughout the collection.

This juxtaposition is particularly evident in the Sonata in E minor HWV 379 (Op 1 No 1a), where the Allegro’s brisk, acrobatic melodies showcase Beznosiuk’s virtuosic flair, yet the subsequent slow movement lingers uneasily, revealing a sense of stasis that tempers the momentum built in the faster sections. The harmonic language, though rich, reveals a tendency of these slow movements to meander without a clear emotional or dramatic purpose.

An intriguing aspect of this recording lies in the interpretive choices made by the performers. Beznosiuk’s deep, resonant tone in the lower register contrasts with the ethereal quality of her upper range, yet there is an overall impression that her interpretive decisions lack the urgency that Handel’s music often demands. While she plays with grace and an admirable control of dynamics, one cannot help but feel a missed opportunity for greater emotional depth and energy, particularly in the more engaging Allegro sections.

In comparison to notable recordings of this repertoire, such as those by Jean-Pierre Rampal or the ensemble Les Arts Florissants under the direction of William Christie, Beznosiuk’s interpretations may come across as comparatively restrained. Rampal’s interpretations, for instance, are often marked by an exuberance that is infectious, whereas Beznosiuk’s performances, though polished, occasionally skirt the edge of tedium—especially in the slower movements, which can evoke a sense of incompleteness.

The engineering of this recording is commendable, with a clear and balanced sound that allows the intricate interplay between flute, cello, and harpsichord to emerge without muddiness. However, the overall sobriety of the sound may contribute to an impression of restraint that does not serve the music’s dramatic potential as effectively as one might hope.

These sonatas, while not the pinnacle of Handel’s output, possess historical significance as they reflect the evolution of instrumental music in the early 18th century. They serve as a bridge between the virtuosic demands of the Baroque period and the expressive potential that would flourish in the Classical era.

In conclusion, while this recording of Handel’s complete flute sonatas by Hyperion showcases the technical proficiency of the performers and the charm of the music, it reveals a tension between the lively fast movements and the languorous slow sections. Beznosiuk’s interpretations, though graceful, could benefit from a greater infusion of energy and emotional nuance to elevate these works beyond mere curiosity for Handel enthusiasts. As it stands, this recording offers a window into Handel’s flute music, but one that is perhaps best approached with tempered expectations.