Composer: Jerry Goldsmith

Composer: Jerry Goldsmith

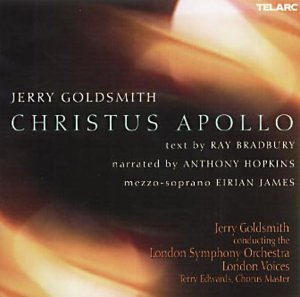

Works: Christus Apollo, Music for Orchestra, Fireworks

Performers: London Symphony Orchestra, Jerry Goldsmith (conductor), Sir Anthony Hopkins (narrator), Eirian James (mezzo-soprano), London Voices

Recording: 3rd – 5th September 2000, Abbey Road Studios, London; Narration recorded 10th October 2000, Sony Music Scoring, Culver City, California

Label: TELARC CD-80560

Jerry Goldsmith, an iconic figure in film scoring, often straddles the line between cinematic narrative and concert hall aspirations. The present recording showcases three distinct works: the dodecaphonic “Christus Apollo” (1969), “Music for Orchestra” (1970), and the more accessible “Fireworks” (1999). Each piece occupies a unique place within Goldsmith’s oeuvre, reflecting both personal and stylistic evolution, yet the disparate qualities of these works raise questions about coherence and emotional impact.

“Fireworks,” composed as a celebratory piece for the Hollywood Bowl, offers a lively, tonal romp that, while engaging, ultimately feels superficial. The orchestration bursts with energy, yet the motifs lack the thematic depth one might expect from a composer of Goldsmith’s caliber. The rhythmic exuberance presents a facade of vitality, but upon deeper exploration, one finds a series of rather banal melodic ideas that do little to elicit lasting engagement. It is as if Goldsmith, in a moment of nostalgia, has crafted a work that is more decorative than substantive. This sentiment is compounded by the realization that the piece could easily serve as background for a visual medium, a notion that might irk Goldsmith’s defenders who seek to elevate his concert works beyond their filmic roots.

In stark contrast, “Music for Orchestra” embraces dodecaphonic techniques, a method often associated with the angst-ridden landscape of mid-20th-century Europe. The work unfolds with a complexity that reflects Goldsmith’s personal turmoil during its composition, a time marked by divorce and familial strife. The twelve-tone rows, while at times dense, provide a structural framework that, paradoxically, allows for emotional expression. Yet, one must contend with the inherent challenges of serial music: the risk of emotional detachment. Goldsmith’s sincerity shines through in his admission that this style was liberating for him, yet the resultant music can feel emotionally vacuous for the listener. One is left pondering the rationale behind each note’s placement, as the sequential relationships seem arbitrary rather than intentional, leading to an overall sense of artistic void.

“Christus Apollo,” set to text by Ray Bradbury, presents yet another stylistic pivot. The philosophical and mystical elements of the text are ambitious, yet the musical setting often lacks the requisite dynamism to convey the intended depth. Goldsmith’s orchestration here is lush but can feel bogged down by an overabundance of solemnity that might overshadow the inherent joyfulness suggested by the text. Sir Anthony Hopkins’ narration provides a welcome contrast, his rich timbre and nuanced delivery bring a palpable warmth to the performance. However, the separation of the narration from the orchestral recording creates a dissonance in scale; Hopkins’ soft-spoken approach feels at odds with the grand orchestral backdrop, raising questions about interpretative choices in the recording process.

Sonically, the recording itself is polished, a hallmark of Telarc’s engineering, with clarity and precision that allow each instrumental line to be discerned. Yet, the high production quality cannot mask the inconsistencies in material. The juxtaposition of tonal ease in “Fireworks” against the more challenging textures of the dodecaphonic works presents a disjointed listening experience. While the orchestral execution is admirable, the emotional resonance of the music often eludes the audience.

Goldsmith’s efforts in this collection reveal a composer grappling with his identity, both as a film composer and a concert musician. While there are moments of brilliance, particularly in the orchestration and the effective narration, the overall impact is muddled by the incongruity of styles and the occasional emotional disconnect. This recording may find its audience among dedicated Goldsmith admirers, yet for those seeking a cohesive artistic statement, it may not fully satisfy. The listener is left to navigate the shifting landscapes of Goldsmith’s musical language, with varying degrees of success.