Composer: Edward Elgar, Johann Sebastian Bach

Composer: Edward Elgar, Johann Sebastian Bach

Works: Violin Concerto, Partita No. 2 in D minor

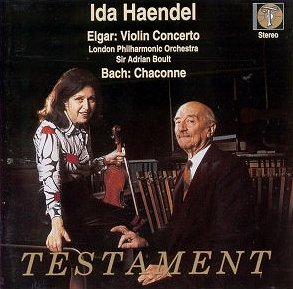

Performers: Ida Haendel (violin), London Philharmonic Orchestra/Sir Adrian Boult

Recording: 24 Apr, 10 May 1977, 10, 15 Jan 1978, Abbey Road Studios, London; Bach recorded Sept 1995, Abbey Road Studio No. 1, London

Label: Testament SBT 1146

The recording of Elgar’s Violin Concerto, alongside Bach’s Partita No. 2 in D minor, provides a compelling juxtaposition of the emotional depth of early 20th-century British music with the intricate counterpoint of the Baroque. Elgar’s concerto, a cornerstone of the violin repertoire, emerged from a period of personal and national reflection after World War I, embodying a poignant sense of loss and longing. Similarly, Bach’s Partita, though centuries older, conveys its own narrative of grace and complexity, showcasing the violin’s capabilities in a more virtuosic context. The choice of Ida Haendel as soloist is particularly fitting, as her artistry has long been associated with both the romantic expressiveness of Elgar and the technical demands of Bach.

Haendel’s interpretation of Elgar’s Violin Concerto is marked by a lush, silvery tone that is immediately captivating. Her phrasing, however, often leans towards the languorous, creating a sense of introspection that can, at times, feel overly reflective. The opening movement, “Allegro,” flows with a broad, sweeping lyricism, yet one might argue that this approach sacrifices some of the dynamic contrast that can heighten the emotional impact. The slow movement, “Andante,” showcases Haendel’s ability to produce a hauntingly beautiful sound, yet this effectiveness is sometimes overshadowed by a pervasive sense of melancholy that threatens to veer into the realm of the excessively sentimental. The finale, “Allegro, non troppo,” while lively, continues this trend of subdued energy, lacking the vigorous drive found in more compelling interpretations, such as Heifetz’s celebrated recording with Sargent.

The orchestral collaboration under Sir Adrian Boult, a distinguished conductor with a deep affinity for Elgar’s music, does offer moments of brilliance. Boult’s direction brings out the lush orchestration that characterizes Elgar, yet one wonders if his advanced age at the time of recording contributed to a certain reticence in interpretation. While the orchestral textures are rich and full, the interplay between soloist and ensemble sometimes feels imbalanced, as if the orchestra is supporting rather than propelling the soloist. The recording quality, captured on analogue 3M tape, is notably vivid, highlighting the warmth of Haendel’s tone and the orchestral colors, though it does not fully compensate for the interpretative shortcomings.

Turning to Bach’s Partita No. 2, recorded nearly two decades later, Haendel’s technical prowess is on full display. The “Ciaccona,” in particular, serves as a showcase for her virtuosic capabilities, with a clear articulation of the intricate lines and a keen sense of musical architecture. The clarity of her bowing and the precision of her fingerwork reveal an artist deeply attuned to the structural complexities of Bach’s writing. Here, the recording quality shines even brighter, presenting a more immediate sound that captures the nuances of Haendel’s performance with remarkable fidelity.

This juxtaposition of Elgar’s deeply emotional landscape with Bach’s rigorous formalism highlights the versatility of Haendel as an artist. While her performance of the Elgar Concerto may not ascend to the heights of the finest recordings available, particularly in its emotional and dynamic spectrum, it remains a testament to her lyrical gifts. The Bach Partita, in contrast, underscores her technical mastery, presenting a compelling case for her artistry in both the romantic and Baroque idioms. Ultimately, while the Elgar may appeal primarily to those seeking to experience Boult’s reflective interpretation of a beloved work, the Bach stands out as a definitive representation of Haendel’s capabilities, showcasing her as a vital interpreter of the violin repertoire.