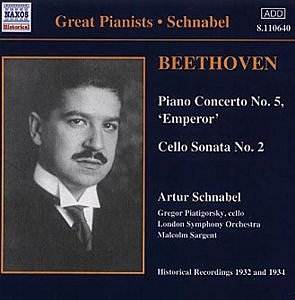

Composer: Ludwig van Beethoven

Composer: Ludwig van Beethoven

Works: Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat, Op. 73, ‘Emperor’; Cello Sonata in G minor, Op. 5 No. 2

Performers: Artur Schnabel (piano), Gregor Piatigorsky (cello), London Symphony Orchestra/Sir Malcolm Sargent

Recording: March 24, 1932 (Emperor); December 6 and 16, 1934 (Cello Sonata), Abbey Road Studios

Label: NAXOS HISTORICAL mono 8.110640

Beethoven’s ‘Emperor’ Concerto, one of the pinnacles of the piano repertoire, stands as a testament to the composer’s innovative spirit and mastery of form. Completed in 1809 amidst the turmoil of the Napoleonic Wars, it encapsulates both the grandeur and introspective depth that characterize Beethoven’s late style. This recording, featuring the legendary Artur Schnabel on piano with the London Symphony Orchestra under Sir Malcolm Sargent, not only revives the work’s historical significance but also illuminates its nuanced emotional landscape.

Schnabel’s interpretation of the ‘Emperor’ exudes a rare blend of technical prowess and lyrical sensitivity. From the outset, the first movement’s exposition reveals Schnabel’s ability to balance the piano’s authority with the orchestra’s contributions. His crystalline articulation of the repeated chords around the ten-minute mark showcases his deftness, while simultaneously allowing the orchestral textures to emerge with clarity. Sargent’s orchestration is attentive, creating a rich tapestry that supports rather than overwhelms Schnabel’s piano, an essential partnership that is often overlooked in modern performances. The slow movement unfolds with a rapt serenity, with Schnabel’s entrance marked by an exquisite descending scale that speaks volumes of his interpretative depth. The mezza voce transition into the finale is particularly arresting, a hallmark of Schnabel’s interpretative choices that invites listeners into a moment of suspended emotion — a quality regrettably absent in many contemporary renditions.

The technical aspects of this performance further enhance its stature. Schnabel’s legato is nothing short of extraordinary; his ability to sustain melodic lines with a seamless flow is particularly evident in the Adagio, where each note is imbued with expressive weight. The recording itself, remastered by Mark Obert-Thorn, reveals surprising detail for a historical document, although the inherent shrillness typical of early recordings can be distracting, especially in orchestral passages. Nevertheless, the warmth of Schnabel’s piano and the articulate contributions of Piatigorsky in the Cello Sonata serve to elevate the listening experience, providing a rich counterpoint to the ‘Emperor.’

Piatigorsky’s performance in the Cello Sonata, while more subdued than Schnabel’s, creates a palpable dialogue between the two instruments. The slow opening movement invites listeners into an intimate chamber music setting, where the interplay of cello and piano becomes a thrilling exploration of thematic development. Piatigorsky’s occasional lapses in intonation are minor in the grand scheme, overshadowed by the overall artistry on display. The ornamentation in the last movement is executed with an organic fluidity, a testament to both musicians’ profound understanding of Beethoven’s intentions.

This recording warrants a place in any serious collection, not only for the historical significance of the artists involved but also for the musical insights it offers. The coupling of the two works, while contrasting, creates a compelling narrative that showcases Beethoven’s versatility as a composer.

Schnabel’s ‘Emperor’ remains a benchmark, reflecting not only the artist’s unparalleled musicianship but also the timeless relevance of Beethoven’s genius. This release from Naxos serves as an essential reminder of the artistry that can emerge from historical recordings, inviting repeated listenings and continued exploration of these masterpieces.