Composer: Elie Siegmeister

Composer: Elie Siegmeister

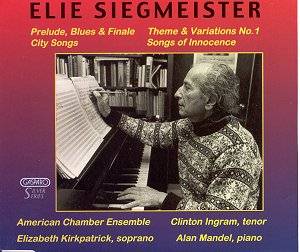

Works: Prelude, Blues and Finale (1984); City Songs (1977); Theme and Variations for solo piano (1932); Songs of Innocence (1972 rev., 1985)

Performers: American Chamber Ensemble & Stanley Drucker; Clinton Ingram, tenor with Alan Mandel, piano; Alan Mandel, piano; Elizabeth Kirkpatrick, soprano with Alan Mandel, piano

Recording: Studio recording 1986 – reissued from Gasparo LP GS-253 in 1999

Label: GASPARO GSS 2008

Elie Siegmeister, an American composer whose career spanned much of the 20th century, remains a somewhat neglected figure in the pantheon of classical music. Despite his notable contributions, especially in the realm of American music, his works have not garnered the widespread recognition of contemporaries like Copland or Bernstein. This collection, featuring performances of four significant works, offers an opportunity to reassess Siegmeister’s contributions, particularly in light of his stylistic evolution and the influences of his formative years studying under Wallingford Riegger and Nadia Boulanger.

The “Theme and Variations for solo piano,” composed when Siegmeister was just 23, stands as a remarkable testament to his early mastery. From the outset, Alan Mandel’s performance reveals a confident command of the piano’s capabilities. The dissonance and rhythmic complexity certainly draw parallels to Prokofiev, yet there is a distinct assertiveness in Siegmeister’s voice that diverges from his predecessors. Mandel navigates the piece’s angular melodies with dexterity, showcasing the work’s energetic drive and structural coherence. The harmonic language, while at times reminiscent of Copland’s “Piano Variations,” remains uniquely Siegmeisterian, reflecting an early affinity for chromaticism that would characterize much of his oeuvre.

Contrastingly, “Songs of Innocence,” which aims to set the poetry of William Blake, does not achieve the same level of success. Here, Elizabeth Kirkpatrick’s soprano, although technically proficient and expressive, is hampered by Siegmeister’s setting. The angularity of the melodic lines, coupled with unresolved harmonies, rather starkly undermines the lyrical qualities of Blake’s text. The intention behind the music—to evoke innocence and simplicity—falls short as the emotional resonance remains elusive. This setting, particularly in the second song “Clouds,” lacks the distinguishing features that would elevate it to memorable heights. Despite the careful attention paid by Mandel in the piano accompaniment, it becomes evident that the composer struggled to adapt his style to the subtleties of the text.

The “Prelude, Blues and Finale,” scored for clarinets and piano, presents a contrasting landscape. Stanley Drucker’s clarinet work in the opening prelude is strikingly Varèsian, characterized by a meticulous exploration of timbre and color. The subsequent movement, “Blues,” while infused with the stylistic markers of blues music, does not fully deliver the expected emotional depth, instead presenting an awkward juxtaposition of styles that ultimately feels unconvincing. The finale, marked by virtuosic piano passages and intricate counterpoint, successfully redeems the piece, showcasing Siegmeister’s ability to craft engaging musical dialogues. Yet, one might argue that this work, while intriguing, reinforces the notion that Siegmeister’s early promise did not translate into a consistently compelling later output.

The recording quality holds up well, with a clear and balanced sound that allows the performers’ nuances to shine through. The engineering effectively captures the warmth of the piano and the rich sonority of the clarinets, although at times the dynamic range could be more pronounced to better reflect the dramatic contrasts inherent in Siegmeister’s writing.

Siegmeister’s music, particularly in this collection, invites both admiration and critique. His early works are imbued with a confidence that hints at a bright future, yet the later compositions often reveal a struggle to reconcile ambition with artistic clarity. This compilation serves as both an introduction and a challenge to listeners: to engage with a composer who, while perhaps overshadowed by his peers, offers a unique voice deserving of deeper exploration.