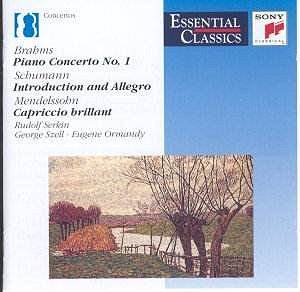

Composer: Johannes Brahms

Composer: Johannes Brahms

Works: Piano Concerto No. 1 (1859), Piano Concerto No. 2 (1881), Introduction and Allegro Appassionato (Schumann, 1849), Capriccio Brillant (Mendelssohn, 1825), Burleske (Strauss, 1886)

Performers: Rudolf Serkin (piano), Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Eugene Ormandy, Cleveland Orchestra conducted by George Szell

Recording: Severance Hall, Cleveland (Brahms: 19-20 Apr 1968; 21-22 Jan 1966), Town Hall, Philadelphia (Schumann: 17 Mar 1964; Mendelssohn: 4 Apr 1967; Strauss: 3 Feb 1966)

Label: Sony Essential Classics

Johannes Brahms, a towering figure of the Romantic period, is often juxtaposed with the likes of Schumann and Mendelssohn, reflecting the stylistic evolution of the 19th century. The Piano Concertos, particularly the First and Second, encapsulate Brahms’s mastery of orchestral and pianistic dialogue, offering an ideal platform for the interpretation of Rudolf Serkin. This recording, featuring performances from both the Cleveland Orchestra under Szell and the Philadelphia Orchestra under Ormandy, presents a compelling exploration of Brahms’s complex emotional landscape, interspersed with the works of other luminaries, thus offering context and contrast.

Serkin’s performance of Brahms’s First Piano Concerto reveals a duality in his interpretative approach. His playing is inherently robust, embodying the “ursine” quality noted in previous critiques, yet he also exhibits a surprising dexterity in the more agile passages. The opening movement’s orchestral introduction is marked by Szell’s incisive direction, showcasing the Cleveland players’ formidable energy and precision. Serkin’s entry, however, is somewhat overshadowed by a sound that lacks the clarity one might expect from this repertoire, with the CBS recording exhibiting a graininess that, while nostalgic, feels slightly constraining. The interplay between pianist and orchestra is compelling, yet the textures occasionally suffer from a lack of definition, particularly in the climactic moments of the first movement.

The Second Piano Concerto, conversely, thrives under Serkin’s touch; the expansive first movement unfolds with a relaxed grandeur. Here, Serkin’s ability to contrast the weighty thematic statements with lighter, more ethereal passages is striking. The orchestral body, while still maintaining a gravelly determination, aligns beautifully with Serkin’s expansive interpretation, creating a cohesive musical tapestry. This concerto exemplifies Brahms’s late style, where lyrical introspection meets a robust structural integrity. Szell’s Cleveland Orchestra, with their meticulous execution, provides the necessary gravitas, allowing Serkin’s interpretations to shine. The finale, infused with a joyful exuberance, serves as a perfect complement to Strauss’s Burleske, which follows suit with its own buoyant spirit.

Schumann’s Introduction and Allegro Appassionato stands as a delightful and rare addition to the program, with Serkin navigating the lyrical passages with a highly romantic and beguiling flair. This work, often overshadowed in the concert repertoire, benefits from Serkin’s nuanced phrasing and emotional depth. The Mendelssohn Capriccio Brillant, however, is less successful in Serkin’s hands. The performance lacks the effervescent quality typical of this piece, with the execution feeling somewhat weighed down, missing the lightness of touch that brings Mendelssohn’s music to life. Comparatively, Joseph Kalichstein’s earlier recording offers a more spirited interpretation, highlighting the fantasy inherent in Mendelssohn’s composition.

Sound quality remains a persistent theme throughout this collection. While the Brahms Second may be deemed essential for its interpretative strengths, those seeking pristine audio may find the original CBS sound somewhat limiting. The engineering, while historically significant, does not capture the full resonance and clarity that modern listeners have come to expect. Nonetheless, the emotional weight carried by the Cleveland strings and the probing intensity of Szell’s conducting are compelling enough to transcend these limitations.

This collection offers a rich tapestry of Brahms’s piano concertos, showcasing Serkin’s formidable artistry. The performances resonate with historical significance and emotional depth, even if they occasionally succumb to the constraints of their recording era. For those who appreciate the raw, powerful expression of Brahms, Serkin’s interpretations, especially of the Second Concerto, are indispensable additions to the discography.