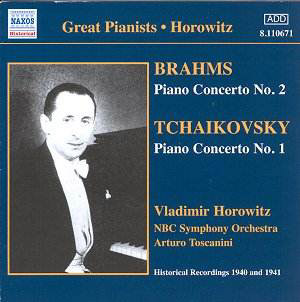

Composer: Johannes Brahms

Composer: Johannes Brahms

Works: Piano Concerto No. 2; Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky – Piano Concerto No. 1

Performers: Vladimir Horowitz, piano; NBC Symphony Orchestra; Arturo Toscanini, conductor

Recording: May 1940 (Brahms); May 1941 (Tchaikovsky)

Label: NAXOS HISTORICAL 8.110671

The juxtaposition of Brahms and Tchaikovsky on this Naxos Historical release, featuring the eminent Vladimir Horowitz alongside the legendary Arturo Toscanini, offers a fascinating glimpse into two distinct yet intertwined musical worlds. Brahms, a stalwart of the Germanic tradition, infuses his Piano Concerto No. 2 with a profound sense of introspection and structural integrity. In stark contrast, Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 bursts forth with fiery passion and emotional immediacy. The historical context of these recordings, made in the early 1940s, further accentuates their significance, capturing not only the artistry of Horowitz but also the interpretative fervor of Toscanini at a time when both were at the zenith of their careers.

The Brahms concerto, however, proves to be a perplexing affair. While Horowitz is often celebrated for his virtuosic technique and interpretative depth, this performance emerges as an exercise in detachment. The opening movement’s emphatic first entry, intended to establish a robust dialogue between piano and orchestra, instead veers into brusqueness. Ian Julier’s sleeve notes aptly describe the performance as “detached” and “reluctant to engage.” Indeed, the choppy rhythms and mechanical phrasing undermine the inherent lyricism of Brahms’s writing. The phrase endings, while crisp, lack the necessary warmth, leaving a sense of enervation rather than engagement. A notable moment is Horowitz’s descending treble run, which, while technically impressive, comes across as overly mischievous, distracting from the music’s gravitas.

The second movement reveals even deeper shortcomings. Here, Toscanini’s rhetorical gestures fail to breathe life into Brahms’s melting melodies, as Horowitz’s playing feels almost metronomic, devoid of the emotional resonance that this lyrical section demands. Even the contributions of cellist Frank Miller, usually a bastion of expressiveness, seem constrained, overshadowed by the performance’s pervasive coldness. Such interpretative choices result in a treatment of Brahms’s music that feels superficial, lacking the rich, self-reflective depth that characterizes the composer’s oeuvre. The finale, while featuring some attractive playing, ultimately succumbs to an air of triviality, rendering a performance that is more about technical display than musical substance.

The Tchaikovsky concerto, recorded a year later, fares somewhat better but still lacks the necessary interpretative fire. Here, the performance opens with a thunderous, almost overwrought zeal that, while initially engaging, quickly reveals itself to be a double-edged sword. There are moments of breathtaking intensity and vibrant color, yet this high-octane approach often teeters on the brink of hysteria. Tchaikovsky’s lush orchestrations and emotive themes demand a nuanced touch that is often lost in the heat of this rendition. A comparison with Rubinstein and Barbirolli’s interpretation highlights how an understanding of the concerto’s emotional landscape can elevate the performance from mere technical prowess to artistic transcendence. While Horowitz and Toscanini offer substantial intensity, the resultant sound can feel excessively bombastic, compromising the concerto’s intricate lyrical qualities.

The recording quality, despite its historical nature, reveals itself as a mixed bag. The restoration efforts mitigate some of the lower frequency muddiness, yet the orchestral balance frequently favors the piano, creating an uneven soundscape that detracts from the overall listening experience. The engineering choices seem to amplify Horowitz’s more aggressive tendencies while neglecting the orchestral texture that Brahms and Tchaikovsky so meticulously crafted.

What emerges from this collection is an intriguing, if flawed, document of two iconic performances that resonate with the ambition of their time yet ultimately fall short of their potential. The Brahms concerto, marred by detachment and mechanical interpretation, lacks the depth required to engage fully with the music’s complexities. Conversely, while Tchaikovsky’s concerto offers flashes of brilliance, it is often overshadowed by an excess of fervor that detracts from its lyrical beauty. Collectively, these recordings serve as a reminder of the heights to which Horowitz and Toscanini could rise, even as they reveal the limitations inherent in their approach to these beloved works.