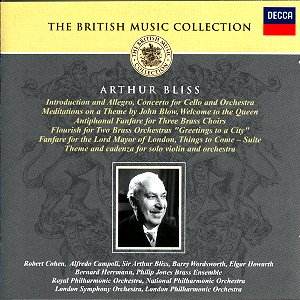

Composer: Sir Arthur Bliss

Composer: Sir Arthur Bliss

Works: Introduction and Allegro; Cello Concerto; Meditations on a Theme by John Blow; Antiphonal Fanfare; Flourish; Welcome to the Queen; Theme and Cadenza for Violin; Suite: Things to Come

Performers: Robert Cohen (cello); Alfredo Campoli (violin); Royal Philharmonic Orchestra; London Philharmonic Orchestra; London Symphony Orchestra; National Philharmonic Orchestra; Philip Jones Brass Ensemble; Conductors: Barry Wordsworth; Bernard Herrmann; Sir Arthur Bliss

Recording: Various dates from 1955 to 1993; Decca 470 186-2 [2CDs: 124.21]

Label: DECCA

The music of Sir Arthur Bliss stands as a testament to the rich tapestry of British composition in the 20th century, often overshadowed by the weight of contemporaries like Elgar and Vaughan Williams. This Decca collection, spanning nearly four decades of Bliss’s output, offers a compelling array of works that showcases his orchestral mastery and unique voice. The recordings, although varied in technology and interpretation, provide an essential insight into the evolution of Bliss’s compositional style and the cultural milieu from which it emerged.

Robert Cohen’s performance in the Cello Concerto is particularly noteworthy. The work, composed in 1945, reflects a blend of lyrical expressiveness and robust orchestration that demands a soloist who can navigate its emotional landscape with both finesse and vigor. Cohen delivers a vibrant interpretation, his tone warm yet incisive, effectively capturing the concerto’s spirited nature. Yet, one cannot help but feel that the concerto’s potential is somewhat eclipsed by the more prominent Elgar Cello Concerto. Bliss’s work, while equally deserving of attention, lacks the same immediate recognition, a fact that this recording endeavors to rectify.

The Introduction and Allegro is a splendid example of Bliss’s adeptness at weaving intricate textures and thematic development. The dual offerings of this piece in the collection—one conducted by Bliss himself and the other by Barry Wordsworth—allow for a fascinating comparison. Bliss’s own interpretation, recorded in 1955, exhibits a visceral energy, marked by a keen awareness of the work’s structural dynamics. Wordsworth’s later recording, although exhibiting superior sonic clarity, feels more restrained, lacking some of the raw passion that Bliss instills. This variance raises questions about interpretive choices and their impact on the listener’s experience.

Among the highlights of this collection is the Meditations on a Theme by John Blow, composed in the mid-1950s. This set of variations, based on the Psalm ‘The Lord is My Shepherd,’ unfolds with an emotional depth that transcends its source material. The theme is revealed gradually, culminating in a poignant climax that showcases Bliss’s ability to blend the old with the new. Wordsworth’s interpretation here, while meticulously crafted, does not quite reach the heights of Richard Handley’s interpretation on EMI, which brings a more evocative phrasing and a greater lyrical sweep to the work.

The contributions of the Philip Jones Brass Ensemble are equally commendable, offering lively renditions of the lighter fare included in the collection. While these pieces may not be considered masterpieces, they serve as delightful interludes that highlight Bliss’s versatility and the ensemble’s technical prowess. The recordings afford an engaging clarity, effectively accentuating the brass’s vibrant sonorities.

Despite its many strengths, the collection does show some inconsistencies in presentation. The booklet notes, while informative, fall short of the comprehensive documentation typically expected from Decca, leaving listeners craving deeper insights into the historical and contextual significance of the works. This lack of thoroughness is a missed opportunity, particularly for those who seek to understand the broader implications of Bliss’s contributions to British music.

The collection ultimately serves as both an introduction and a reaffirmation of Bliss’s significance within the canon of British classical music. While it does not offer a fully rounded portrait—due in part to the occasional overlap of works and a few missed opportunities in documentation—it succeeds in drawing attention to a composer whose works deserve greater exposure. The recordings present a compelling case for Bliss’s music, inviting listeners to explore the nuanced textures and emotional depths of his compositions. The collection earns commendation as a valuable resource for both seasoned aficionados and newcomers alike, eager to delve into the rich legacy of a truly remarkable British composer.