Composer: Ludwig van Beethoven

Composer: Ludwig van Beethoven

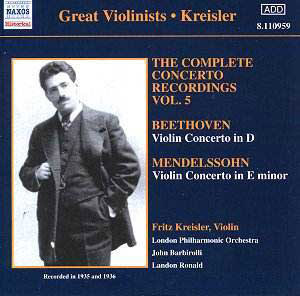

Works: Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61; Felix Mendelssohn, Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64

Performers: Fritz Kreisler, violin; London Philharmonic Orchestra; John Barbirolli (Beethoven); Landon Ronald (Mendelssohn)

Recording: June 1936 (Beethoven); April 1935 (Mendelssohn) at Abbey Road Studio No. 1, London, UK

Label: NAXOS HISTORICAL 8.110959

Both Beethoven and Mendelssohn stand as titans of the violin concerto repertoire, their works embodying distinct yet complementary approaches to the genre. Beethoven’s Violin Concerto, completed in 1806, is a monumental reflection of the transition from the Classical to the Romantic era, characterized by its expansive structure and profound emotional depth. Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, finished in 1844, offers a more lyrical and virtuosic model, showcasing a melodic brilliance and intricate interplay between soloist and orchestra. This recording, featuring the legendary Fritz Kreisler, draws upon performances captured in the mid-1930s, a period ripe with interpretative exploration yet fraught with the limitations of early recording technology.

Kreisler’s interpretation of the Beethoven concerto is notable for its historical significance but suffers from considerable technical shortcomings. The opening passages reveal a striking lack of precision; Kreisler’s intonation falters, particularly during the first rising entry, where sour notes disturb the otherwise noble trajectory of the music. This technical fallibility is not merely an occasional misstep; it is persistent enough to detract from the overall experience. While Kreisler’s artistry is revered, in this performance, it seems overshadowed by the challenges of execution, particularly in the rapid passagework that demands pristine intonation. Despite these issues, the slow movement does present moments of calm and introspection, though they are often marred by excessive portamento and an apparent lack of the structural clarity that modern performances tend to emphasize. Barbiolli’s conducting, while sympathetic to Kreisler’s interpretative choices, allows the performance to feel pulled and uneven, lacking the cohesive narrative that characterizes more recent interpretations.

In comparison, the Mendelssohn concerto fares somewhat better, although it too is not without its flaws. The initial interaction between conductor and soloist reveals a marked difference in tempo choices, with Kreisler’s impulsive energy clashing with Ronald’s more measured approach. This discrepancy leads to moments of tension that could be interpreted as either spontaneity or a lack of cohesion, depending on one’s perspective. Intonation issues persist, though they are less pronounced than in the Beethoven performance. The andante, marked for its lyrical beauty, is taken at a brisk tempo that, while invigorating, sacrifices some of the melodic poise that is typically expected. This performance lacks the enchanting magic often associated with the transition between the slow movement and the finale, where a sense of fantasy is crucial. The finale, while technically solid, lacks the requisite wit and fire that would elevate it beyond mere competence.

Sound quality, as one might expect from recordings of this vintage, reveals limitations inherent in the era’s technology. The orchestral texture often feels constricted, with the violin occasionally overshadowed by the ensemble, resulting in a less-than-ideal balance. While historical recordings can offer a glimpse into the interpretative practices of past generations, they often fall short of the clarity and detail available in contemporary recordings.

The allure of this disc lies primarily in its historical context and the opportunity to experience Kreisler, a figure of considerable renown. However, for those seeking definitive performances of these beloved concertos, one might more readily turn to modern interpretations. Artists such as Kyung Wha Chung or Hilary Hahn offer nuanced, technically assured readings that uphold the music’s integrity while delivering the emotional weight that is so essential. Kreisler’s performances, while undoubtedly valuable for their historical significance, do not ultimately satisfy the demands of these works as they stand in today’s concert repertoire. The listener’s expectations for both technical precision and interpretative depth may lead them elsewhere when reaching for Beethoven or Mendelssohn.