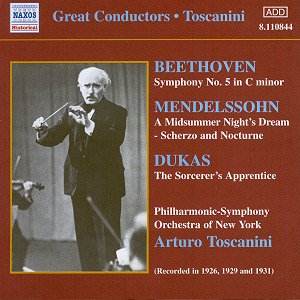

Composer: Ludwig Van Beethoven

Composer: Ludwig Van Beethoven

Works: Symphony No. 5; Felix Mendelssohn, A Midsummer Night’s Dream op. 61, Scherzo and Nocturne; Paul Dukas, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice

Performers: Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra of New York, Arturo Toscanini

Recording: 1926-1931

Label: NAXOS

Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 stands as a monumental pillar in the orchestral repertoire, symbolizing the struggle against fate with its iconic four-note motif. This recording by Arturo Toscanini with the Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra of New York, captured between 1926 and 1931, offers a glimpse into the interpretative choices of a conductor whose career was as electrifying as it was uncompromising. Toscanini’s approach to this symphony is emblematic of his philosophy: precision, intensity, and an unyielding drive towards clarity of expression.

In examining the performance of the Fifth Symphony, one cannot overlook the historical context. Recorded in the shadow of a world recovering from the devastation of the First World War, Toscanini’s interpretation imbues the work with a sense of urgency and resilience. The first movement, marked Allegro con brio, is notable for its brisk tempo and fierce articulation. Toscanini’s insistence on clarity in the orchestral lines brings forth the inner voices of the strings and woodwinds, allowing the thematic material to emerge with an almost surgical precision. However, the recording’s technical limitations—certain sonic compressions and audible disruptions—occasionally detract from the intended power. The coughs and extraneous noise, while a reminder of the live performance context, can disrupt the immersive experience.

The coupling of Mendelssohn’s Scherzo and Nocturne from A Midsummer Night’s Dream reveals a contrasting interpretative landscape. Here, the conductor’s earlier 1926 recording demonstrates a certain lethargy that feels at odds with the spirited nature of Mendelssohn’s music. The Scherzo, despite its buoyancy, lacks the requisite lightness and finesse, presenting a reading that feels somewhat heavy-footed. By the time of the 1929 recording, Toscanini’s confidence seems to have blossomed, yet the two takes remain almost identical, suggesting a hesitance to fully explore the dynamic possibilities inherent in the score. The presence of flautist John Amans highlights the delicate interplay of textures, yet the overall performance feels constrained and needs more effervescence.

Paul Dukas’s The Sorcerer’s Apprentice is perhaps the most notable example of Toscanini’s technical prowess. The conductor’s trademark brisk tempos and vivid articulation galvanize the orchestra into a display of virtuosity that is simultaneously thrilling and, to some, overly showy. While some may appreciate this exuberant display, it occasionally overshadows the nuanced storytelling that Dukas intended. The orchestral color and energy are undeniable, yet the interpretative choices risk overshadowing the delicacy and narrative flow of the piece.

NAXOS’s commitment to presenting these historical recordings is commendable, and the efforts of producer Mark Obert-Thorn in restoration are evident, though one cannot escape the limitations of the original recording technology. The clarity achieved is impressive, yet the occasional sonic artifacts serve as a reminder of the era. When comparing these interpretations to more contemporary recordings, the differences in sonic fidelity and interpretative scope are marked. Modern conductors often embrace a broader palette of dynamics and phrasing, which can render Toscanini’s readings as somewhat rigid by today’s standards.

The performances captured in this collection present a fascinating, if uneven, portrait of Toscanini’s artistry. While the Beethoven Fifth remains a compelling interpretation of a monumental work, it is the contrasting energies of Mendelssohn and Dukas that provide a more complex picture of the conductor’s interpretative range. Each work reveals different facets of Toscanini’s approach, from the intense clarity of Beethoven to the more variable interpretations of Mendelssohn and Dukas. This recording, while not without its flaws, serves as an important historical document, reflecting both the triumphs and limitations of one of the 20th century’s most influential conductors.