Composer: Baroque

Composer: Baroque

Works: Trio Sonata in G, BWV 530; Inventions Nos 4, 8, and 13; Chorale, Wach Auf; Allemande from French Suite No 2; Sonata in E Minor; A New Ground; Ah! How Sweet it is to Love; Music For a While; Sonata Cu Cu; Folies; Lady Ann Bothwel’s Lament; Solo called the Cuckoo

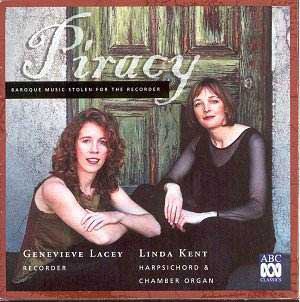

Performers: Genevieve Lacey, recorder; Linda Kent, harpsichord and chamber organ

Recording: ABC – ANTIPODES SERIES – 472 226-2 [59’34”]

Label: ABC Classics

Baroque music, characterized by its intricate counterpoint and rich ornamentation, has always invited a range of interpretations and arrangements. This latest release, “Music Stolen for the Recorder,” presents a fascinating exploration of works originally conceived for other instruments, primarily the keyboard. The title’s nod to “piracy” cleverly underscores the practice of transcription, which has been a vital aspect of musical evolution, especially during the Baroque period. It is particularly fitting that much of this collection draws heavily from the works of J. S. Bach, whose compositions, while rooted in their own instrumental contexts, lend themselves beautifully to the unique timbre of the recorder.

Genevieve Lacey’s interpretation of the selected pieces is compelling, as she deftly navigates the technical demands of the recorder with both finesse and interpretive depth. The opening Trio Sonata in G, BWV 530, showcases Lacey’s agility, particularly in the lively interplay between the melodic lines. Her use of varied recorder types, including the voice flute and treble, enriches the tonal palette, allowing for nuances that breathe new life into the familiar works. The transcriptions of Bach’s Inventions, particularly Nos. 8 and 13, highlight not only Lacey’s virtuosic technique but also her capacity to evoke the playful spirit inherent in Bach’s writing. However, one might argue that the essence of these keyboard works is somewhat diluted in translation, as the polyphonic complexity can occasionally be simplified through the lens of the recorder.

Linda Kent’s accompaniment on the harpsichord and chamber organ is judiciously supportive, providing a solid harmonic foundation that complements Lacey’s lines. The recording’s engineering captures the nuances of both instruments effectively, with Kent’s crisp articulation on the harpsichord standing in clear contrast to the warm, breathy tones of the recorder. This balance is particularly evident in Purcell’s “A New Ground,” where the vocal origins of the piece resonate through Lacey’s expressive phrasing, demonstrating how well the recorder can translate the emotive qualities of song.

Among the lesser-known works featured, Schmelzer’s “Sonata Cu Cu” and Finch’s “Solo called the Cuckoo” emerge as standout tracks. These pieces, less commonly encountered in the standard repertoire, allow Lacey to showcase her interpretive skills in a fresh context. The lively nature of Schmelzer’s work, with its playful motifs and dynamic shifts, benefits from Lacey’s energetic performance, while Finch’s lament evokes a somber beauty that underlines Lacey’s interpretive range. The recording’s clear sound allows the listener to appreciate the subtleties of phrasing and dynamics, although a touch more warmth in the lower register could have enhanced the overall sonority.

The anthology’s final tracks, featuring Marin Marais and Geminiani, provide a contemplative conclusion to the program. Marais’s “Folies” particularly stands out with its rich variations, where Lacey’s deft ornamentation and Kent’s fluid accompaniment combine to create an absorbing dialogue. Geminiani’s “Lady Ann Bothwel’s Lament,” originally a violin piece, hauntingly translates to the recorder, revealing Lacey’s ability to capture the piece’s melancholic essence. These selections offer a compelling argument for the versatility of the recorder, while simultaneously inviting a comparative reflection on the original settings.

“Music Stolen for the Recorder” serves as an engaging entry point into the Baroque repertoire, though it may not fully replace the experience of the original works. Lacey’s articulate playing and Kent’s supportive accompaniment are commendable, yet the listener is often reminded of the inherent strengths of the original compositions. This recording stands as a testament to the adaptability of Baroque music, while also affirming the unique voice that the recorder brings to the table, making it a worthy listen for both enthusiasts and casual listeners alike.