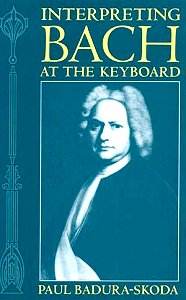

Composer: Paul Badura-Skoda

Composer: Paul Badura-Skoda

Works: Interpreting Bach at the Keyboard

Performers: Paul Badura-Skoda (piano, fortepiano, harpsichord)

Recording: Oxford University Press, 1990 (Book Review)

Paul Badura-Skoda’s “Interpreting Bach at the Keyboard” emerges as a pivotal contribution to the discourse surrounding the performance of Johann Sebastian Bach’s keyboard works. This seminal text, drawing upon Badura-Skoda’s extensive career as a pianist, fortepianist, and harpsichordist, serves as both a reflective memoir and an analytical treatise on the complexities inherent in Bach’s music. Written in the context of an era that grapples with authenticity versus modernity in performance practice, Badura-Skoda’s insights offer a bridge between scholarly research and practical musicianship, thus illuminating the often contentious debates over instrument choice and interpretative strategies.

Central to Badura-Skoda’s examination is the perennial question of instrument selection. He deftly navigates the historical landscape of keyboard instruments, elucidating how the harpsichord, clavichord, and fortepiano each imbue Bach’s compositions with distinct tonal colors and expressive possibilities. The author’s non-dogmatic approach permits a dialogue between various performance practices rather than imposing a singular “authentic” method. For instance, he discusses the unique resonance of the fortepiano, which, while capable of dynamic nuance, might sacrifice some of the percussive clarity inherent in harpsichord performances. This nuanced exploration invites performers to consider the interpretative implications of their instrument choices, making the text invaluable not only to musicians but also to listeners eager to grasp the subtleties of Bach’s sound world.

Badura-Skoda’s analytical rigor is particularly evident in his discussions of tempo and ornamentation. His detailed examination of 18th-century notational practices, such as barrel rolls, provides invaluable insights into how tempo might be understood beyond modern metronomic constraints. This historical context enriches our appreciation of Bach’s music as a living tradition, where tempo was subject to the whims of performers who sought to breathe life into the written score. The expansive section on ornamentation stands out as a particularly challenging yet rewarding endeavor. Here, Badura-Skoda meticulously catalogs the various ornament types, offering performers a roadmap through the intricate landscape of Baroque embellishments. His presentation of musical examples allows readers to grasp the practical implications of these ornaments, which are essential for an authentic realization of Bach’s keyboard music.

The sound quality and engineering of the book’s presentation—while not directly applicable to conventional recordings—reflect a high standard of scholarly publishing. The clarity with which Badura-Skoda articulates complex ideas, combined with a cohesive structure, enhances the work’s accessibility. Although much of this text is tailored for keyboard performers, the lucid explanations of historical context and interpretive choices make it an engaging read for any aficionado of Bach’s music. This duality of purpose—serving both the performer and the interested listener—is a hallmark of Badura-Skoda’s pedagogical philosophy.

The depth of analysis found within “Interpreting Bach at the Keyboard” solidifies its status as an essential resource for musicians delving into Bach’s oeuvre. By marrying historical insight with practical advice, Badura-Skoda champions a thoughtful, informed approach to performance that resonates well beyond the page. For those seeking to enrich their understanding and appreciation of Bach’s keyboard works, this text not only illuminates the pathways of interpretation but also invites a deeper connection to the music itself, ensuring its place as a cornerstone in the study of Baroque performance practice.